This article is referring to the flattened shark species Squatina squatina, also known as the “angelshark.” For the “other” monkfish, see the anglerfish article. The monkfish, or angelshark, is a critically endangered species of shark native to the coasts of the northeast Atlantic Ocean. They have flattened bodies, much like stingrays do, with an almost arrow-like body shape. Read on to learn about the monkfish.

Description of the Monkfish

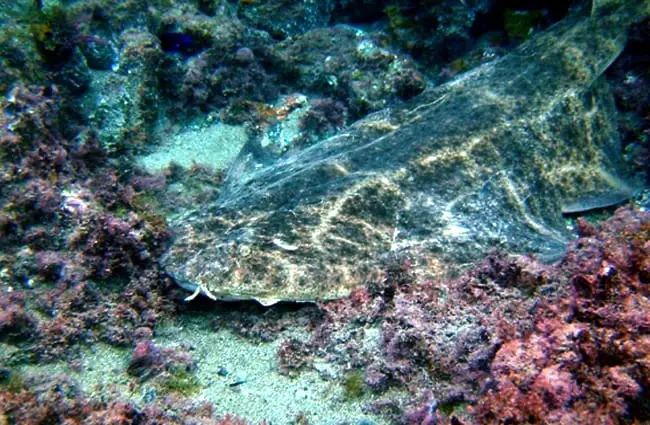

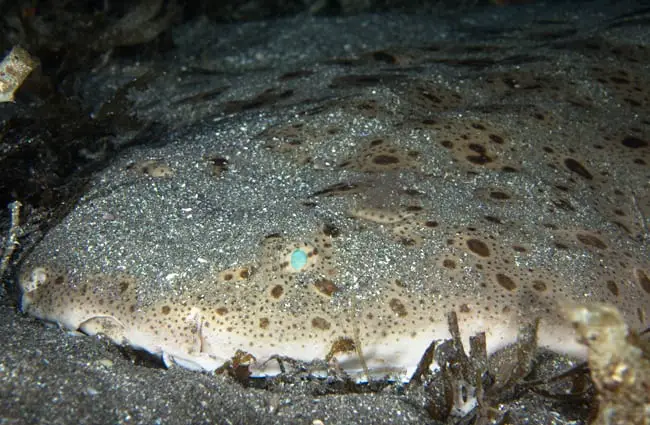

This species of shark is incredibly odd-looking. This species of shark is one of the largest in its family, and can reach lengths nearly 8 ft. long. It looks almost like a cross between a stingray and a rug that got sucked into the vacuum.

Their long sides are actually extensive pectoral fins, and another set of fins large triangular fins follow them. They also have two small dorsal fins located just before the tail fin. This is a shark that you really have to see to believe.

Interesting Facts About the Monkfish

This strange shark species is just as interesting as it looks. Sadly, their populations are in severe decline due to human activity. Learn more about why these cool creatures need your help below.

- A Fish of Many Names – These sharks lay claim to a number of names, including monkfish, angelsharks, and even sand devils. An animal with the nickname sand devil and angelshark? Now that’s ironic!

- Sit and Wait – This species, like all angel sharks, are ambush predators. They bury themselves just beneath the sand or mud and wait for prey to stray too close. Spotted colors, which match the sand they hide beneath, cover their skin.

- In the Blink of an Eye – As with most ambush predators, monkfish can strike with lighting-fast speed. They shoot up at a 90º angle, and strike their prey before it knows what’s hit it. It takes just 1/10 of a second for them to catch their prey.

- Topside – When you are buried beneath the sand, it can be a little difficult to see what’s going on above you. Thankfully, monkfish have eyes perched right on top of their head. When they bury themselves, just their eyes peak through the sand. This lets them see when prey is approaching. Other ambush predators, like American alligators, have similarly placed eyes.

Habitat of the Monkfish

Because they have such a specific hunting behavior, they must live in areas soft enough for them to bury themselves. This means they prefer areas where the bottom consists of sand or mud. They primarily live along the continental shelf, close to shore and in relatively shallow waters. Individuals will position themselves near reefs and other areas with plentiful fish.

Distribution of the Monkfish

Sadly, humans have exterminated this species of shark from much of its previous range. They used to live across virtually all of the temperate seas in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean.

Before humans pushed them to the brink of extinction, you could find this species from Sweden, all the way to the coast of the Sahara Desert, and out to the Canary Islands. Nowadays, they no longer reside in the North Sea, and are nearly absent from the northern Mediterranean.

Diet of the Monkfish

The motto of the monkfish, and most other angel sharks, is “if it swims too close, and it fits in my mouth, I’ll eat it!” Of course, because they hide on the sea floor, the vast majority of their prey are bottom-dwelling organisms.

Some of their most common prey include skates, stingrays, flounders, and other flatfishes. They will also eat other fish, squid, crabs, and invertebrates. If the shark finds a good spot, it will stay there and hunt for several days before moving on to a new hunting ground.

Monkfish and Human Interaction

When left alone, these sharks rarely bother anyone. If they are approached, they will either sit still and hide, or swim away. However, they are more than capable of inflicting painful bites if trapped or attacked. This is especially true of specimens caught in fishermen’s nets. Sadly, this occurs often, both on purpose and as bycatch.

For decades humans have captured this species for its oil, skin, meat, and fins. Becoming trapped in nets for other fish species is the direst threat to the species. Unfortunately for monkfish, they do not reproduce quickly enough to make up for this decimation. The IUCN lists this species as Critically Endangered.

Domestication

Humans have not domesticated this species in any way.

Does the Monkfish Make a Good Pet

No, monkfish do not make good pets. They are critically endangered, and every individual is important for the survival of the species. Even if they weren’t, housing this large of a fish requires a huge aquarium and lots of money to feed it!

Monkfish Care

The only captive breeding program of this species is at Deep Sea World in North Queensferry, UK. This program has successfully bred the monkfish in captivity, producing live pups for the first time in 2011.

This program is important for the survival of the species, as captive breeding research can help other facilities successfully breed the species as well. Reintroduction of captive-bred animals to the wild has been successful for black footed ferrets, California condors, and a number of other species. Hopefully the same will be true of monkfish.

Behavior of the Monkfish

This species of shark is generally quite sedentary, and spends most of its time resting just beneath the sand or on the bottom of the sea floor. They are slightly more active at night, and will sometimes swim just above the bottom to move to a new hunting site.

Their most active behavior occurs over their migration. In the winter the sharks migrate south for warmer waters, and in the summer they migrate north again.

Reproduction of the Monkfish

Monkfish are viviparous, and give birth to live young. The female breeds once every two years, and can give birth to a litter of 7 – 25 pups. The gestation period is 8 – 10 months long, and the pups are around 10 in. long at birth. They are fully independent, and receive no maternal care.

Females cannot reproduce until they reach 4.3 – 5.6 ft. in length. This is one of the primary reasons that these sharks are so endangered. When humans kill large numbers of adults, there simply aren’t enough sexually mature individuals to replenish the population.

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-238x178.jpg)

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-100x75.jpg)