The ocean depths hold countless mysteries, and among its most enigmatic inhabitants is the Box Jellyfish. Often misunderstood and sometimes feared, these fascinating creatures, belonging to the class Cubozoa, represent a pinnacle of invertebrate evolution in many respects. Far from being simple blobs, Box Jellyfish are active predators with complex sensory systems and potent venoms, making them subjects of intense scientific study and popular intrigue. This article delves into the intricate world of the Box Jellyfish, exploring its biology, behavior, ecological role, and its often-dramatic interactions with humans.

An Introduction to the Cubozoans: The Box Jellyfish

Box Jellyfish are not your typical jellyfish. While they share the general cnidarian body plan, their distinctive cube-shaped bell, advanced visual capabilities, and highly potent venom set them apart. These attributes allow them to be efficient hunters in their marine environments, navigating with a precision uncommon among their gelatinous relatives. Their scientific classification as Cubozoa underscores their unique morphology, distinguishing them from true jellyfish (Scyphozoa) and other cnidarian classes like Hydrozoa and Anthozoa.

Where Do Box Jellyfish Live? Habitat and Distribution

Box Jellyfish are predominantly found in tropical and subtropical waters around the globe. Their preferred habitats include coastal areas, estuaries, and shallow waters, often near mangroves or river mouths. These environments provide ample food sources and protection for their early life stages. While some species are widespread, others have more restricted ranges.

- Indo-Pacific Region: This is the hotspot for Box Jellyfish diversity and abundance. Species like the infamous Chironex fleckeri, often called the “sea wasp,” are prevalent along the northern coasts of Australia, Southeast Asia, and parts of the Indian Ocean.

- Atlantic Ocean: Several species inhabit the warmer parts of the Atlantic, including the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico.

- Pacific Ocean: Beyond the Indo-Pacific, Box Jellyfish can be found in various Pacific islands, including Hawaii, and along the coasts of Central and South America.

- Specific Locations for Observation: For those hoping to observe these creatures in their natural habitat, coastal regions of Queensland and the Northern Territory in Australia during the wet season (October to May) are known for high concentrations. However, extreme caution is advised due to their venomous nature. Other locations include the waters off Thailand, the Philippines, and parts of Japan.

Physical Characteristics: A Masterpiece of Marine Engineering

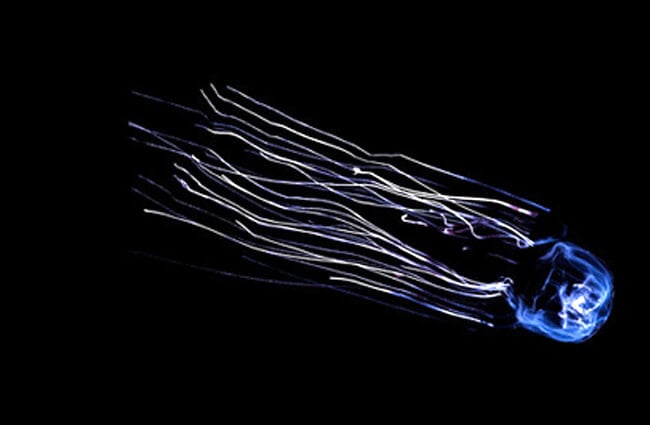

The most striking feature of a Box Jellyfish is its bell, which is square or box-shaped when viewed from above, hence its common name. This bell can range in size from a few centimeters to over 30 centimeters in diameter, depending on the species. From each of the four corners of the bell, a pedalium, a muscular stalk, extends, from which numerous tentacles dangle. These tentacles can be remarkably long, stretching up to 3 meters in some large species like Chironex fleckeri, and are laden with millions of stinging cells called nematocysts.

Perhaps the most astonishing feature is their visual system. Box Jellyfish possess up to 24 eyes, arranged in clusters of six on each side of their bell. These eyes are not all the same: some are simple pit eyes that detect light, while others are complex, lens-bearing eyes capable of forming images. This sophisticated visual apparatus allows them to navigate complex environments, detect obstacles, and actively hunt prey, a stark contrast to the passive drifting of most other jellyfish.

Diet and Predation: Active Hunters of the Reef

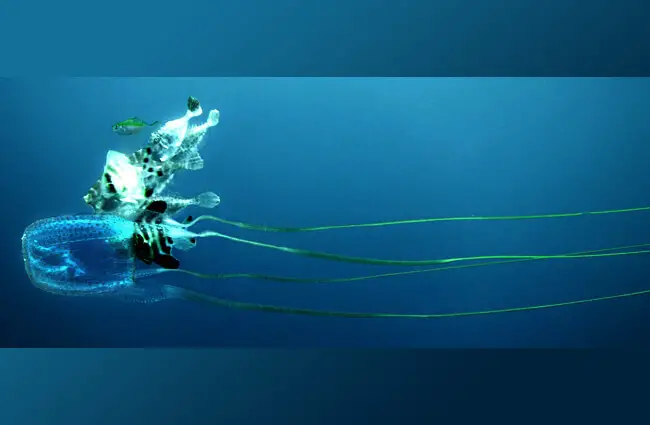

Unlike many jellyfish that passively filter feed or drift into prey, Box Jellyfish are active and agile predators. Their advanced visual system and powerful swimming capabilities enable them to pursue and capture prey with remarkable efficiency.

- Primary Diet: Their diet primarily consists of small fish and crustaceans, such as prawns and shrimp. They use their long, venomous tentacles to ensnare and paralyze their victims before bringing them to their mouth, located on the underside of the bell.

- Hunting Strategy: Box Jellyfish often patrol specific areas, using their vision to spot prey. Once a target is identified, they can rapidly contract their bell to propel themselves towards it. The venom delivered by their nematocysts is incredibly fast-acting, quickly incapacitating even relatively large prey.

- Ecosystem Role: As active predators, Box Jellyfish play a significant role in their ecosystems by controlling populations of small fish and crustaceans. They are an important link in the food chain, transferring energy from lower trophic levels to higher ones.

Reproduction and Life Cycle: A Metamorphosis of Marvels

The life cycle of a Box Jellyfish, like many cnidarians, involves both sexual and asexual reproduction and distinct larval and polyp stages. However, the details vary among species.

- Sexual Reproduction: Adult Box Jellyfish are typically dioecious, meaning there are separate male and female individuals. They release sperm and eggs into the water, where fertilization occurs externally.

- Planula Larva: The fertilized egg develops into a free-swimming planula larva. This ciliated larva eventually settles on a suitable substrate, often in sheltered coastal areas like mangrove roots or rocks.

- Polyp Stage: The planula metamorphoses into a sessile (attached) polyp. Unlike the polyps of many other jellyfish, Box Jellyfish polyps do not bud off medusae directly. Instead, they undergo a process called strobilation.

- Metamorphosis to Medusa: In a remarkable transformation, the entire polyp body metamorphoses into a single, tiny medusa (the adult jellyfish form). This process is unique to Cubozoa and distinguishes them from Scyphozoa, where polyps typically produce multiple medusae through strobilation. The young medusa then detaches and begins its free-swimming life, growing into the adult Box Jellyfish.

This complex life cycle, with its distinct stages and unique metamorphosis, highlights the evolutionary adaptations that allow Box Jellyfish to thrive in diverse marine environments.

Evolutionary History: An Ancient Lineage with Modern Adaptations

Box Jellyfish belong to the phylum Cnidaria, an ancient group of animals that includes corals, sea anemones, and other jellyfish. The fossil record for soft-bodied creatures like jellyfish is sparse, making their evolutionary history challenging to trace. However, molecular studies suggest that Cubozoa diverged from other cnidarian lineages hundreds of millions of years ago, likely in the Precambrian or early Cambrian periods.

Their unique characteristics, such as the box-shaped bell, advanced eyes, and direct metamorphosis from polyp to medusa, represent significant evolutionary innovations. These adaptations allowed them to become highly effective predators, filling a distinct ecological niche. The development of complex vision, in particular, is a remarkable example of convergent evolution, where similar traits evolve independently in different lineages, as seen in the eyes of vertebrates and cephalopods.

Interaction with Humans: A Potent Presence

The interaction between Box Jellyfish and humans is almost exclusively defined by their potent venom. While most species are relatively harmless, a few, particularly Chironex fleckeri and the Irukandji jellyfish (several species within the genera Carukia and Malo), are among the most venomous animals on Earth.

The Sting: A Medical Emergency

A Box Jellyfish sting can range from intensely painful to rapidly fatal, depending on the species and the amount of venom injected. The venom of Chironex fleckeri is cardiotoxic, neurotoxic, and dermatonecrotic, meaning it affects the heart, nervous system, and skin. Symptoms can include:

- Excruciating pain

- Rapid onset of cardiovascular collapse

- Respiratory distress

- Skin necrosis and scarring

Irukandji stings, while often less immediately fatal, can cause a severe and delayed reaction known as Irukandji syndrome, characterized by:

- Severe muscle cramps

- Excruciating back and limb pain

- Nausea and vomiting

- Profuse sweating

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Tachycardia (rapid heart rate)

- A feeling of impending doom

What to Do if Stung by a Box Jellyfish

Immediate action is crucial after a Box Jellyfish sting. The following steps are generally recommended:

- Call for Medical Help: Dial emergency services immediately.

- Do NOT Rub the Area: Rubbing can cause more nematocysts to fire, releasing more venom.

- Apply Vinegar: Pour liberal amounts of vinegar (acetic acid) over the stung area for at least 30 seconds. Vinegar helps to neutralize unfired nematocysts, preventing further venom release. This is a critical first aid step for most Box Jellyfish stings, especially Chironex fleckeri.

- Remove Tentacles: Carefully remove any remaining tentacles using tweezers or a gloved hand. Do NOT use bare hands.

- Monitor the Victim: Observe for signs of shock, respiratory distress, or cardiac arrest. Be prepared to administer CPR if necessary.

- Pain Management: Once medical help arrives, pain relief and specific antivenom (if available and indicated for the species) will be administered.

Important Note: While vinegar is effective for many Box Jellyfish species, it may exacerbate stings from some Irukandji species. However, in regions where both are present, vinegar is generally recommended as the primary first aid due to the higher immediate fatality risk of Chironex fleckeri. Always seek professional medical advice.

Box Jellyfish in Human Culture

Due to their dangerous nature, Box Jellyfish have largely been viewed with apprehension and fear in human culture. They are often featured in news reports about beach closures and marine hazards. However, their unique biology also inspires scientific curiosity, leading to documentaries and popular science articles that highlight their complex eyes and potent venom as wonders of the natural world. In some coastal communities, warnings and protective measures, such as stinger nets and “stinger suits,” have become a part of beach culture during peak seasons.

Conservation Status: A Thriving Predator

Currently, most Box Jellyfish species are not considered endangered or threatened. Their populations appear stable, and in some areas, they may even be increasing, possibly due to factors like overfishing of their predators or competitors, and changes in ocean conditions. They are highly adaptable and prolific, allowing them to maintain robust populations in their preferred habitats.

Caring for Box Jellyfish in Captivity: A Zookeeper’s Challenge

Keeping Box Jellyfish in captivity is a specialized task, primarily undertaken by advanced aquariums and research institutions. Their delicate nature, specific environmental requirements, and potent venom present unique challenges.

- Specialized Tank Design: Box Jellyfish require kreisel or “roundabout” tanks. These tanks have a circular flow that keeps the jellyfish suspended in the water column without being damaged by tank walls or equipment. Sharp corners and strong currents must be avoided.

- Water Quality: Pristine water quality is paramount. Stable temperature, salinity, pH, and ammonia/nitrite/nitrate levels must be maintained within narrow parameters. Advanced filtration systems are essential.

- Feeding: They require a constant supply of live prey, such as enriched brine shrimp, copepods, or small fish, depending on the species and size. Feeding must be done carefully to ensure the jellyfish captures the food without damaging its delicate tentacles.

- Handling: Direct handling is strictly avoided due to the venom. Specialized tools and nets are used, and zookeepers must wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), including thick gloves and eye protection.

- Environmental Enrichment: While jellyfish do not typically require “enrichment” in the traditional sense, maintaining a stable, clean, and appropriately lit environment that mimics their natural habitat is crucial for their well-being.

- Breeding Programs: Some institutions successfully breed Box Jellyfish, requiring careful management of polyp stages and metamorphosis.

The dedication required to care for these animals underscores their biological complexity and the respect they command from those who study them up close.

Fascinating Facts About Box Jellyfish

Beyond their reputation, Box Jellyfish hold a trove of intriguing biological details:

- The “Sea Wasp”: Chironex fleckeri is often referred to as the “sea wasp” due to its potent sting and rapid action.

- Irukandji Syndrome: Named after the Irukandji people of northern Queensland, who described the symptoms of stings from these tiny jellyfish long before Western science identified the culprits.

- Active Swimmers: Unlike many jellyfish that drift, Box Jellyfish can swim at speeds of up to 6 meters per minute, actively pursuing prey.

- Complex Nervous System: They possess a more centralized nervous system than other jellyfish, contributing to their advanced behaviors.

- No Brain, Yet Vision: Despite lacking a centralized brain, their sophisticated eyes allow for complex visual processing, including obstacle avoidance and potentially even object recognition.

- Rhopalia: The clusters of eyes are located on structures called rhopalia, which also contain statocysts for balance and orientation.

- Venom Research: The unique composition of Box Jellyfish venom is a subject of intense medical research, with potential applications in pharmacology.

- Transparency: Many species are almost completely transparent, making them incredibly difficult to spot in the water, a perfect camouflage for an ambush predator.

- Rapid Growth: Box Jellyfish can grow remarkably fast, especially during their medusa stage, quickly reaching adult size.

Conclusion: A Marvel of Marine Biology

The Box Jellyfish, with its cube-shaped bell, advanced visual system, and potent venom, stands as a testament to the incredible diversity and evolutionary ingenuity of life in our oceans. From its intricate life cycle and active predatory lifestyle to its significant impact on human health, this cnidarian challenges our conventional understanding of what a jellyfish can be. While caution is always warranted when encountering these creatures in the wild, their study offers invaluable insights into neurobiology, vision, and venom research, solidifying their place as one of the most compelling subjects in marine biology.

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-100x75.jpg)