Unearthing the Mastodon: A Prehistoric Giant

For millennia, mastodon bones have surfaced in fields and riverbeds, sparking curiosity and wonder. The mastodon, a creature often confused with its relative the mammoth, was a magnificent herbivore that roamed North and Central America for millions of years. This guide delves into the fascinating world of the mastodon, exploring its history, biology, behavior, and lasting legacy.

What Was a Mastodon

The mastodon was not a single species but a group of extinct proboscideans—the order that also includes elephants, mammoths, and gomphotheres. While often visualized alongside the woolly mammoth in popular culture, the mastodon represents a distinct lineage. Key differences lie in their teeth. Mastodons possessed cone‑shaped bumps on their molars, ideally suited for browsing on leaves and twigs, whereas mammoths had ridged molars for grazing on grasses. This dietary specialization shaped their environments and ultimately, their fates.

Physical Characteristics

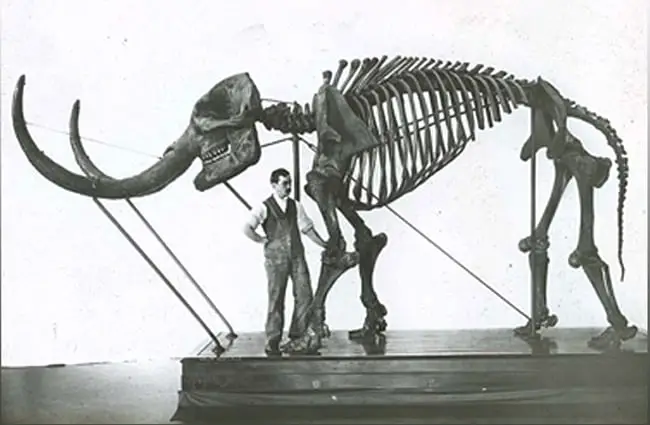

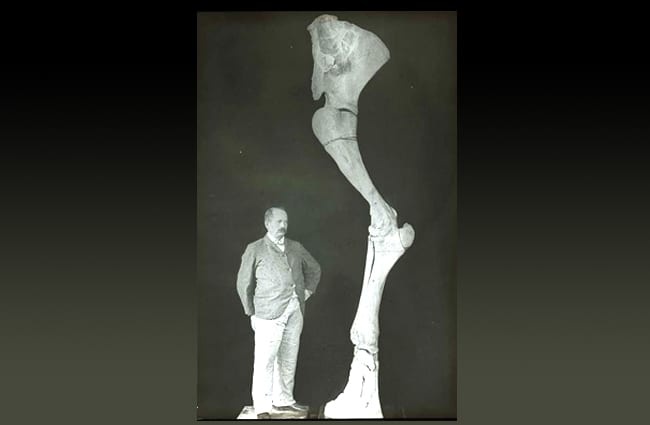

Mastodons were imposing creatures. Generally, they stood between 7 and 10 feet tall at the shoulder, comparable in size to modern African elephants, though often somewhat smaller. Their weight ranged from 4 to 6 tons. They possessed a robust build supported by thick, pillar‑like legs. Unlike mammoths, mastodons did not have the iconic long, curved tusks. They had straight or slightly curved tusks, and in some species only males bore them. Their bodies were covered in a coat of coarse hair that insulated them against cold climates.

A Journey Through Time: Evolution and Habitat

The history of the mastodon stretches back millions of years. The earliest mastodon ancestors appeared in Africa during the Miocene epoch, approximately 27 million years ago. From there, they dispersed into North America, arriving around 15 million years ago. Several species of mastodon evolved, adapting to different environments. The American mastodon, Mammut americanum, is the most well‑known species and the one typically referenced when discussing these prehistoric giants.

During the Pleistocene epoch, often referred to as the Ice Age, mastodons thrived in a variety of habitats. They preferred forested areas, particularly those with abundant wetlands, bogs, and lakes. These environments provided their preferred food sources—leaves, twigs, shrubs, and aquatic vegetation. Fossil evidence suggests they were widespread across eastern and central North America, from the Great Lakes region down to Florida, and as far west as the Great Plains.

Diet and Feeding Habits

As browsing specialists, mastodons had a unique impact on their ecosystems. Their cone‑shaped molars were perfectly adapted for crushing leaves and twigs. They used their powerful trunks to manipulate branches and pull vegetation toward their mouths. Paleobotanical studies, analyzing plant remains found in fossilized stomach contents and dung, reveal a diet rich in conifers, hardwoods, and aquatic plants.

Unlike grazers, who consume large quantities of low‑nutrient grasses, browsers require less overall food volume. Mastodons likely spent a significant portion of their day foraging, moving through forested areas to find sufficient sustenance. This browsing behavior helped shape forest composition, preventing dense undergrowth and promoting a more open woodland structure.

Social Behavior, Reproduction, and Life Cycle

Determining the social behavior of extinct animals is challenging, but fossil evidence and comparisons to modern elephants offer clues. Mastodons likely lived in small, family groups led by a matriarch, similar to modern elephants. These groups provided protection from predators and facilitated cooperative rearing of young.

Reproduction likely occurred year round, with females giving birth to a single calf after a gestation period of approximately 14 to 15 months. Calves were dependent on their mothers for several years, learning essential survival skills. Mastodons likely had a relatively slow reproductive rate, making them vulnerable to population decline during periods of environmental stress. Their lifespan is estimated to have been around 60 to 70 years.

Mastodons and Their Ecosystem

Mastodons played a crucial role in shaping the Pleistocene ecosystems of North America. As browsers, they controlled forest undergrowth, creating openings that benefited other species. Their foraging activities dispersed seeds, contributing to plant diversity. Their dung provided nutrients for soil enrichment.

Mastodons coexisted with a variety of other Ice Age megafauna, including mammoths, saber‑toothed cats, giant ground sloths, and dire wolves. They were likely preyed upon by these predators, especially when young or weakened. Their presence also influenced the distribution and behavior of other herbivores, creating a complex web of ecological interactions.

Extinction and Human Interaction

Around 11,000 years ago, the mastodon, along with many other megafauna species, disappeared from North America. The exact cause of their extinction remains uncertain. The most widely accepted theory suggests a combination of factors, including climate change at the end of the Pleistocene and increased hunting pressure from early human populations.

Evidence of human interaction with mastodons comes from archaeological sites across North America. Fossilized mastodon bones have been found with stone tools embedded in them, indicating that humans hunted and butchered these animals for food. Mastodon bones were also used to construct shelters and create tools. The extent to which human hunting contributed to their extinction remains a topic of research.

Mastodons in Culture

For centuries, Native American cultures have revered the mastodon. Stories, art, and ceremonial practices often depict these magnificent creatures. Mastodon bones were considered sacred objects, possessing spiritual power.

In modern times, the mastodon continues to capture the imagination of people around the world. Fossil discoveries have fueled scientific research and provided insights into the past. Mastodon skeletons are popular exhibits in museums, inspiring awe and wonder in visitors. The mastodon has also become a symbol of prehistoric life, appearing in books, movies, and other forms of media.

Encountering a Mastodon: A Guide for Hikers (Hypothetical)

Let’s be clear: you won’t encounter a live mastodon! They are extinct. However, if you stumble upon a fossilized bone while hiking, the best course of action is to leave it undisturbed and report your find to a local museum or paleontological society. Removing fossils can damage them and disrupt valuable scientific research.

Caring for Mastodons in Captivity (Hypothetical)

Also hypothetical! But if, somehow, mastodons were brought back from extinction, their care would be incredibly demanding. They would require vast amounts of browse, specialized veterinary care, and extensive space to roam. Their social needs would have to be carefully addressed, providing opportunities for interaction with other mastodons.

Prioritizing enrichment would be crucial, providing stimulating activities to prevent boredom and promote physical and mental well‑being. A team of experienced animal caretakers, paleontologists, and veterinarians would be essential to ensure their welfare.

The story of the mastodon is a reminder of the incredible diversity of life that once existed on Earth. By studying these ancient creatures, we can learn about the past, understand the present, and better prepare for the future.

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-238x178.jpg)

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-100x75.jpg)