The Ubiquitous Mallard: A Feathered Success Story

From bustling city parks to tranquil wilderness wetlands, the Mallard Duck, Anas platyrhynchos, is arguably the most recognizable and widespread duck species on Earth. Its adaptability, striking beauty, and familiar quack have made it a beloved fixture in human landscapes and a fascinating subject for naturalists and scientists alike. This article delves into the remarkable world of the Mallard, exploring its biology, behavior, ecological role, and profound connections with humanity.

Meet the Mallard: Identification and Basic Biology

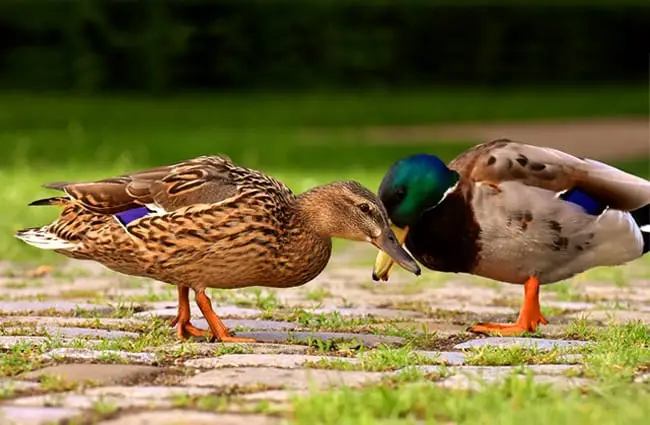

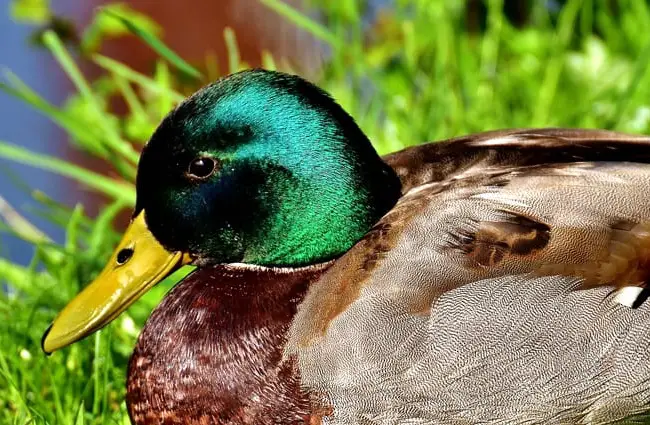

Identifying a Mallard is often straightforward, particularly the male, known as a drake. Drakes boast an iridescent green head, a bright yellow bill, a white neck ring, and a chestnut breast. Their body plumage is a mix of grey, brown, and black, culminating in distinctive curled black tail feathers. The female, or hen, presents a more subdued, mottled brown plumage, offering excellent camouflage during nesting. Both sexes share a vibrant blue speculum, a patch of feathers on the secondary wing feathers, bordered by white stripes, which is visible in flight or when the wings are slightly open. Mallards are medium-sized ducks, typically weighing between 1.5 and 3.5 pounds, with a wingspan of about 35 to 39 inches.

Their vocalizations are equally distinctive. While the classic “quack” is most often associated with the Mallard, it is predominantly the female who produces this loud, descending series of calls. Males have a softer, raspier call, often described as a “rab-rab” sound, and a whistle used during courtship.

A Global Citizen: Mallard Habitat and Distribution

The Mallard’s success story is largely due to its incredible adaptability, allowing it to thrive across a vast geographical range. Native to temperate and subtropical regions of North America, Europe, Asia, and North Africa, it has also been introduced to Australia, New Zealand, and South America. These ducks are not picky about their aquatic environments, inhabiting almost any wetland area. This includes freshwater ponds, lakes, rivers, marshes, and even brackish estuaries. Critically, they are highly tolerant of human presence, frequently found in urban and suburban parks, golf courses, and agricultural lands, as long as there is access to water and vegetation for shelter.

While many Mallard populations are resident year-round, northern populations undertake impressive migrations to warmer climates during winter months, often covering hundreds or thousands of miles. They are strong, fast flyers, capable of reaching speeds up to 55 miles per hour, making these journeys efficient and effective.

The Mallard’s Menu: A Dabbler’s Delight

Mallards are classic “dabbling ducks,” meaning they feed primarily by tipping their bodies forward, submerging their heads and necks to reach food just below the water’s surface, while their tails remain comically pointed skyward. They rarely dive completely underwater for food. Their diet is remarkably diverse and opportunistic, making them omnivores with a flexible palate. This dietary versatility is another key to their widespread success.

- Plant Matter: Seeds, aquatic vegetation, grasses, roots, and agricultural grains like corn and wheat form a significant portion of their diet.

- Invertebrates: They readily consume insects, insect larvae, snails, slugs, and crustaceans.

- Small Vertebrates: Occasionally, they might eat small fish or tadpoles.

Their feeding habits play a crucial role in aquatic ecosystems, helping to control insect populations and disperse plant seeds. However, in urban environments, their diet can become skewed by human handouts, often leading to nutritional deficiencies and health problems.

From Courtship to Clutch: The Mallard’s Reproductive Journey

The Mallard breeding season typically begins in late winter or early spring. Courtship is an elaborate affair, with drakes engaging in a series of head-bobs, tail-wags, and ritualized displays to attract hens. While Mallards are generally considered seasonally monogamous, forming pair bonds for a single breeding season, drakes are known to seek additional mating opportunities, sometimes forcefully, which can be a challenging aspect of their social dynamics.

Once a pair bond is established, the hen takes on the primary responsibility for nesting and raising the young. She constructs a well-hidden nest, usually a shallow depression lined with grass, leaves, and down feathers, often near water but sometimes surprisingly far away in dense vegetation. A typical clutch consists of 8 to 13 pale green or buff-colored eggs. The hen incubates the eggs for approximately 28 days. During this period, she is incredibly vulnerable and relies on her cryptic coloration for camouflage.

Mallard ducklings are precocial, meaning they are born covered in down, with open eyes, and are able to walk and swim within hours of hatching. They follow their mother to water almost immediately, where she teaches them to forage. The ducklings are vulnerable to predators such as snapping turtles, large fish, raptors, and mammals, and only a fraction survive to fledge, typically within 50 to 60 days. The mother Mallard is fiercely protective, guiding her brood and defending them from perceived threats.

Evolutionary Roots: Tracing the Mallard’s Ancestry

The Mallard holds a unique place in avian evolution, particularly concerning its relationship with humans. It is widely considered the ancestor of nearly all domestic duck breeds, with the exception of the Muscovy duck. Evidence suggests that domestication began thousands of years ago in Southeast Asia, with humans selectively breeding Mallards for various traits like meat production, egg laying, and ornamental purposes. This long history of domestication has led to a remarkable diversity in domestic ducks, all stemming from the wild Mallard.

Furthermore, the Mallard is known for its propensity to hybridize with other duck species, including American Black Ducks, Mottled Ducks, and Hawaiian Ducks. While this demonstrates a close genetic relationship between these species, extensive hybridization can sometimes pose a conservation concern for rarer duck populations, as it can dilute their unique gene pools.

Ecosystem Engineer: The Mallard’s Role in Nature

Beyond its aesthetic appeal, the Mallard plays several vital roles within its ecosystem. As an omnivore, it helps regulate populations of aquatic insects and other invertebrates. Its consumption of seeds and subsequent dispersal through droppings contributes to plant propagation, influencing vegetation patterns in wetlands. Mallards also serve as a food source for a variety of predators, including foxes, raccoons, skunks, snapping turtles, and various raptors like hawks and eagles. Their presence can also influence the behavior and distribution of other waterfowl species, sometimes leading to competition for resources or nesting sites.

Mallards and Humanity: A Shared Landscape

The Mallard’s close proximity to human settlements has fostered a complex relationship, intertwining the duck with human culture and daily life.

- Cultural Significance: Mallards frequently appear in folklore, art, and literature, often symbolizing nature, tranquility, or the arrival of spring. Their distinctive appearance makes them popular subjects for wildlife photography and illustration.

- Human Interaction:

- Urban Adaptation: Mallards have masterfully adapted to urban environments, often becoming quite tame around people. This adaptability allows them to thrive in areas where other wildlife struggles.

- Feeding Ducks: A common pastime in parks, feeding ducks, particularly bread, is unfortunately detrimental to their health. Bread offers little nutritional value and can lead to “angel wing,” a deformity that prevents flight. It also contributes to water pollution and can attract pests. Responsible interaction involves observing from a distance and appreciating their natural behaviors without intervention.

- Hunting and Conservation: Mallards are a popular game bird, and their populations are managed through hunting regulations. Despite hunting pressure, their high reproductive rate and adaptability ensure stable populations across much of their range. Conservation efforts focus on wetland preservation, which benefits Mallards and countless other species.

Observing Mallards in the Wild: Tips for Enthusiasts

For animal lovers and aspiring zoologists hoping to observe Mallards, they are one of the easiest ducks to find. Look for them in almost any body of freshwater, from small puddles to large lakes, especially those with vegetated edges. City parks with ponds are excellent starting points. The best times for observation are typically dawn and dusk when they are most active in foraging. During the breeding season, observe courtship displays and watch for hens with broods of ducklings.

When encountering Mallards in the wild, the best practice is to observe from a respectful distance. Avoid approaching nesting females or broods, as this can cause stress and potentially lead to nest abandonment or separation of ducklings from their mother. Never feed wild ducks, as this can lead to dependency, malnutrition, and aggression among birds. Simply enjoy their natural beauty and behaviors without interference.

Caring for Mallards in Captivity: A Zookeeper’s Guide

For zookeepers or those managing captive waterfowl collections, providing optimal care for Mallards involves understanding their specific needs.

- Habitat Requirements:

- Spacious Enclosure: Mallards require ample space, ideally with a large, clean water source for swimming, bathing, and dabbling. A pond or large pool with filtration is essential.

- Shelter: Provide sheltered areas, such as sheds or dense vegetation, to protect them from harsh weather and predators.

- Substrate: Ground cover should be easy to clean and provide good drainage.

- Dietary Management:

- Balanced Pellets: A high-quality waterfowl or duck pellet should form the cornerstone of their diet, providing essential nutrients.

- Supplements: Supplement with fresh greens, vegetables, and occasional insects. Grit should always be available to aid digestion.

- Avoidance: Absolutely avoid feeding bread, processed human foods, or excessive amounts of corn, which can lead to nutritional imbalances and health issues like angel wing.

- Social Structure:

- Mallards are social birds and thrive in groups. However, monitor drakes during breeding season for aggression towards hens or other drakes, especially if space is limited.

- Health and Welfare:

- Regular Checks: Implement a routine health check schedule, looking for signs of illness, injury, or parasites.

- Water Quality: Maintain excellent water quality to prevent disease.

- Wing Clipping/Pinioning: For flight containment, wing clipping (temporary) or pinioning (permanent) may be necessary, performed by a qualified professional.

- Breeding Programs:

- Provide secluded nesting sites with appropriate materials. Monitor clutches and consider artificial incubation if natural incubation is unsuccessful or for population management.

- What to Avoid:

- Overcrowding, which leads to stress and disease.

- Poor sanitation and stagnant water.

- Inappropriate diet.

- Unnecessary handling or disturbance, which can cause stress.

Fascinating Mallard Facts

- The male Mallard’s vibrant green head is not due to green pigment, but rather to structural coloration, where the microscopic structure of the feathers reflects light in a way that appears green.

- Mallards have an impressive ability to navigate, using the sun, stars, and the Earth’s magnetic field during migration.

- In captivity, Mallards can live for over 20 years, significantly longer than their typical wild lifespan of 5 to 10 years.

- They possess a specialized bill with lamellae, comb-like structures that filter small food particles from the water.

- Mallards are one of the few duck species where the male has a distinct curled feather on its tail, a key identifier.

- Their ability to hybridize with so many other duck species makes them a fascinating subject for genetic studies.

The Mallard Duck, with its striking appearance, adaptable nature, and widespread presence, truly embodies a success story in the avian world. From its evolutionary journey to its intricate ecological role and its enduring connection with human society, this common duck offers a wealth of knowledge and endless opportunities for observation and appreciation. Its continued thriving serves as a testament to its resilience and a reminder of the vibrant biodiversity that enriches our planet.

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-238x178.jpg)

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-100x75.jpg)