In the vast tapestry of life, some of the smallest threads can weave the most significant stories. Among these diminutive yet impactful creatures is the deer tick, Ixodes scapularis. Often misunderstood and sometimes feared, this tiny arachnid plays a far more complex role in our ecosystems and lives than its size might suggest. From its ancient lineage to its intricate life cycle and its profound interactions with wildlife and humans, the deer tick is a marvel of adaptation and a subject of intense scientific study.

Unveiling the Deer Tick: A Closer Look

The creature we commonly call the deer tick is scientifically known as Ixodes scapularis. Despite its name, it is not an insect but an arachnid, closely related to spiders and mites. These tiny organisms are ectoparasites, meaning they live on the exterior of their hosts, feeding on blood. Their small size, especially in the nymph stage, makes them particularly difficult to spot, contributing to their reputation as stealthy vectors of disease.

Physical Characteristics and Identification

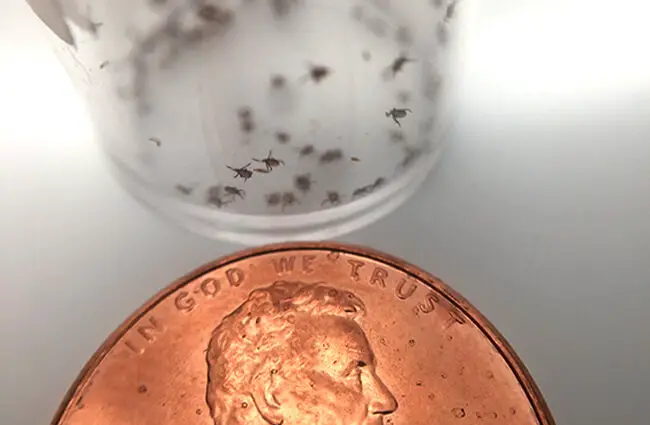

- Size: Adult deer ticks are quite small, typically about the size of a sesame seed (2-3 mm). Nymphs are even smaller, comparable to a poppy seed (less than 1 mm), while larvae are barely visible to the naked eye.

- Color: Adults are generally reddish-brown with a darker, almost black scutum (a shield-like plate on their back). Engorged females can appear grayish-blue.

- Legs: Like all arachnids, they possess eight legs in their nymph and adult stages. Larvae have six legs.

- Sexual Dimorphism: Adult females are larger than males and have a smaller scutum, allowing their bodies to expand significantly when engorged with blood. Males have a scutum that covers most of their back.

Where the Wild Ticks Roam: Habitat and Distribution

Understanding where deer ticks live is crucial for anyone venturing into their territory. These adaptable creatures thrive in specific environmental conditions, making certain regions and habitats hotspots for their presence.

Geographic Range

The primary distribution of Ixodes scapularis spans the eastern and midwestern United States, extending into parts of southeastern Canada. Their range has been expanding, influenced by factors such as climate change, reforestation, and the increasing populations of their primary hosts, particularly white-tailed deer.

Preferred Habitats

Deer ticks are not found just anywhere. They prefer environments that offer both moisture and ample opportunities to find hosts. Key habitats include:

- Woodlands and Forests: Deciduous and mixed forests provide the ideal microclimate with shade, humidity, and leaf litter.

- Tall Grasses and Brushy Areas: The edges of forests, overgrown fields, and areas with dense undergrowth are prime locations. Ticks often “quest” from these vantage points.

- Leaf Litter: This provides shelter from desiccation and predators, especially during overwintering.

- Urban and Suburban Green Spaces: Parks, gardens, and even residential lawns adjacent to wooded areas can harbor tick populations, especially where deer or other wildlife frequent.

For an animal lover or aspiring zoologist hoping to observe a deer tick in its natural environment, focusing on these areas during warmer months, particularly spring and early summer, will increase the chances. However, it is paramount to prioritize personal safety and take all necessary precautions against tick bites.

The Cycle of Life: Diet and Reproduction

The life cycle of the deer tick is a fascinating, multi-stage journey, each step dependent on a blood meal from a suitable host. This parasitic lifestyle is central to their survival and their role in disease transmission.

A Four-Stage Journey

- Egg: Female ticks lay thousands of eggs in the spring, typically in leaf litter. These eggs hatch into larvae.

- Larva: Larvae emerge in the summer. They are tiny, six-legged, and seek their first blood meal, often from small mammals like mice or birds. If the host is infected, the larva can acquire pathogens.

- Nymph: After feeding, the larva molts into an eight-legged nymph. Nymphs are active in late spring and early summer and are responsible for the majority of human tick-borne disease transmissions due to their small size and high infection rates. They seek a second blood meal, often from small to medium-sized mammals, including humans.

- Adult: The nymph molts into an adult tick. Adults are active in the fall and spring. They typically feed on larger hosts, most notably white-tailed deer, which are crucial for their reproduction.

The Blood Meal: A Parasitic Diet

Deer ticks are obligate hematophages, meaning blood is their sole source of nutrition. Each active stage (larva, nymph, adult) requires a single blood meal to molt to the next stage or, in the case of adult females, to lay eggs. This feeding process can last for several days, during which the tick remains attached to its host. It is during these prolonged feeding periods that pathogens, if present in the tick, can be transmitted to the host.

Mating and Reproduction

Mating typically occurs on the host during the adult stage. The male tick finds a feeding female on a deer or other large mammal. After mating, the engorged female detaches from the host, drops to the ground, and over several weeks, lays a clutch of thousands of eggs in a protected location, usually within leaf litter. The female then dies, completing her life cycle. This prolific egg-laying ensures the continuation of the species, despite the high mortality rates at each life stage.

Ecosystem Interactions: More Than Just a Pest

While often viewed solely as a vector of disease, the deer tick is an integral, albeit small, component of its ecosystem. Its interactions with other animals are complex and far-reaching.

Hosts and Pathogens

Deer ticks are generalist feeders, especially in their larval and nymph stages, feeding on a wide variety of birds and mammals. This broad host range is critical for the spread of pathogens. For instance, white-footed mice are often considered the primary reservoir for the bacterium that causes Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi. Ticks acquire the bacteria from infected mice and can then transmit it to other hosts, including humans.

Food Web Contribution

While not a primary food source for many animals, ticks can be consumed by certain birds, spiders, and predatory insects. However, their contribution to the food web is relatively minor compared to their role as disease vectors. Their primary ecological impact stems from their ability to transmit pathogens, which can affect the health and population dynamics of various wildlife species.

The Role of Deer

White-tailed deer are crucial for the adult stage of the deer tick’s life cycle, providing the necessary blood meal for females to reproduce. While deer do not typically harbor the Lyme disease bacterium, they are essential for tick population maintenance and dispersal. Areas with high deer populations often correlate with higher tick densities and, consequently, increased risk of tick-borne diseases.

The Human Connection: Risks, Prevention, and Response

For humans, the most significant interaction with deer ticks revolves around the health risks they pose. Deer ticks are notorious for transmitting several serious diseases, making awareness and prevention paramount.

Diseases Transmitted by Deer Ticks

- Lyme Disease: Caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, it is the most common tick-borne illness in the Northern Hemisphere. Symptoms can include a characteristic “bull’s-eye” rash (erythema migrans), fever, fatigue, and if untreated, can lead to joint pain, neurological problems, and heart issues.

- Anaplasmosis: Caused by the bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum, symptoms include fever, headache, muscle aches, and malaise.

- Babesiosis: Caused by the parasite Babesia microti, it infects red blood cells and can cause flu-like symptoms, particularly severe in immunocompromised individuals.

- Powassan Virus Disease: A rare but serious viral infection that can cause encephalitis or meningitis, with no specific treatment available.

Prevention is Key for Hikers and Outdoor Enthusiasts

Encountering a deer tick in the wild is a common occurrence in endemic areas. Knowing what to do before, during, and after outdoor activities is vital.

- Before You Go:

- Wear Protective Clothing: Long sleeves and pants, tucked into socks, can create a barrier. Light-colored clothing makes ticks easier to spot.

- Use Tick Repellents: Products containing DEET, picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus are effective. Permethrin-treated clothing offers additional protection.

- Stay on Trails: Avoid walking through tall grass, brush, and leaf litter.

- After Your Activity:

- Perform a Thorough Tick Check: Inspect all parts of your body, especially warm, moist areas like armpits, groin, behind the knees, and scalp. Check children and pets too.

- Shower Within Two Hours: This can help wash off unattached ticks.

- Tumble Dry Clothes: High heat can kill any remaining ticks on clothing.

What to Do If You Find a Tick

If a hiker finds an attached deer tick, prompt and proper removal is essential to minimize disease transmission risk.

- Use Fine-Tipped Tweezers: Grasp the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible.

- Pull Upward with Steady, Even Pressure: Do not twist or jerk the tick, as this can cause the mouthparts to break off and remain in the skin.

- Dispose of the Tick: Place it in a sealed bag or container, wrap it tightly in tape, or flush it down the toilet. Do not crush it with bare fingers.

- Clean the Bite Area: Wash the area thoroughly with soap and water or rubbing alcohol.

- Monitor for Symptoms: Keep an eye on the bite area and your overall health for several weeks. Consult a healthcare provider if a rash develops or flu-like symptoms appear.

Fascinating Facts About the Deer Tick

Beyond their reputation, deer ticks hold many intriguing biological secrets:

- Tiny Travelers: Despite their lack of wings, deer ticks can travel significant distances by hitching rides on migratory birds, contributing to their expanding geographic range.

- Overwintering Wonders: Deer ticks are remarkably resilient. They can survive freezing temperatures by burrowing into leaf litter, emerging again when conditions warm.

- Slow Eaters: A single blood meal can take several days to complete, allowing ample time for pathogen transmission.

- Questing Behavior: Ticks do not jump or fly. Instead, they climb onto vegetation and extend their front legs, waiting to grab onto a passing host. This behavior is called “questing.”

- Not Just Deer: While “deer tick” is a common name, these ticks feed on a wide variety of hosts, from mice and birds to raccoons, coyotes, and humans. Deer are primarily important for adult tick reproduction.

- Long Lifespan: A deer tick can live for up to two years, completing its entire life cycle over this period, with long dormant phases between blood meals.

- Salivary Secrets: Tick saliva contains a cocktail of compounds that numb the bite site, prevent blood clotting, and suppress the host’s immune response, allowing the tick to feed undetected for extended periods.

Deeper Dives: Evolution and Captive Care

For aspiring zoologists and those seeking a more expert understanding, the deer tick’s evolutionary history and the intricacies of its captive care for research offer compelling insights.

An Ancient Lineage: Evolution History

Ticks are ancient arachnids, with fossil records dating back tens of millions of years. Their evolutionary journey has been one of specialized adaptation to a parasitic lifestyle. They evolved sophisticated mouthparts for piercing skin and feeding on blood, along with complex salivary gland functions to manipulate host physiology. The co-evolution between ticks, their diverse hosts, and the pathogens they transmit is a dynamic and ongoing process, shaping both tick biology and the epidemiology of tick-borne diseases. Their success lies in their remarkable ability to survive in diverse environments and exploit a wide range of hosts across their multi-stage life cycle.

Caring for Ticks in Captivity: A Research Perspective

While not typically subjects for public display in zoos, deer ticks are routinely maintained in specialized laboratories for scientific research. A zookeeper or lab technician caring for a deer tick colony would perform highly specific tasks, focusing on replicating natural conditions and ensuring biosafety.

- Environmental Control:

- Humidity: Maintaining high humidity (typically 90-95%) is crucial to prevent desiccation, as ticks are highly susceptible to drying out.

- Temperature: Optimal temperatures vary by life stage but are generally kept within a specific range (e.g., 20-25°C) to facilitate development and activity.

- Substrate: Ticks are often kept in containers with a moist substrate, such as plaster of Paris or filter paper, to maintain humidity.

- Feeding Protocols:

- Host Animals: Live animals, such as rabbits, guinea pigs, or mice, are commonly used as hosts for feeding ticks. Strict ethical guidelines and veterinary care are paramount.

- Artificial Feeding Systems: Researchers also utilize artificial membrane feeding systems, which allow ticks to feed on blood through a synthetic membrane, reducing the need for live animal hosts.

- Timing: Ticks are fed at specific intervals corresponding to their life cycle stages, ensuring they receive adequate blood meals to molt or lay eggs.

- Breeding and Colony Maintenance:

- Egg Collection: Engorged females are isolated to lay eggs, which are then collected and incubated under controlled conditions.

- Life Stage Separation: Different life stages (larvae, nymphs, adults) are often kept in separate containers to prevent cannibalism and facilitate research.

- Genetic Management: For long-term colonies, genetic diversity might be managed to prevent inbreeding depression.

- Biosafety and Handling:

- Containment: Ticks, especially those infected with pathogens, are handled in biosafety cabinets within secure laboratory environments to prevent escape and exposure.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Gloves, lab coats, and sometimes respirators are used to protect personnel.

- Avoidances: Direct skin contact with ticks should always be avoided. Exposure to uncontrolled environmental conditions (e.g., low humidity) must be prevented to ensure tick survival.

Conclusion: A Call for Awareness

The deer tick, Ixodes scapularis, is a testament to nature’s intricate design. Far from being a mere nuisance, it is a creature with a fascinating biology, a critical role in its ecosystem, and a significant impact on human health. By understanding its habitats, life cycle, and interactions, we can better protect ourselves and appreciate the complex web of life that surrounds us. Whether you are a student researching its evolutionary past, an animal lover exploring the outdoors, an aspiring zoologist delving into its biology, a hiker seeking safe passage, or a researcher maintaining a vital colony, knowledge about the deer tick empowers us to coexist more safely and intelligently with this tiny, yet mighty, arachnid.

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-100x75.jpg)