The Ocean’s Unsung Heroes: Unveiling the Secrets of Sea Cucumbers

Beneath the waves, amidst the vibrant coral reefs and the silent, crushing depths of the abyssal plains, lies a creature often overlooked yet profoundly important: the sea cucumber. Far from being a mere vegetable of the sea, these fascinating echinoderms are vital engineers of marine ecosystems, possessing an array of bizarre adaptations and a history stretching back millions of years. Prepare to dive deep into the world of these enigmatic invertebrates, discovering why they are so much more than meets the eye.

What Exactly is a Sea Cucumber?

Basic Biology and Classification

Sea cucumbers belong to the phylum Echinodermata, a group that also includes sea stars, sea urchins, and sand dollars. Their scientific name, Holothuroidea, hints at their unique form. Unlike their spiny cousins, sea cucumbers possess a soft, cylindrical body, often described as worm-like or sausage-shaped, with a leathery skin that can be smooth, warty, or spiky. They exhibit a modified form of radial symmetry, typically with five rows of tube feet running along their bodies, which they use for locomotion and attachment. Lacking a true brain, their nervous system consists of a nerve ring around the mouth and nerve cords extending throughout the body. Despite their seemingly simple appearance, their internal anatomy is complex, featuring a unique water vascular system that powers their tube feet and tentacles.

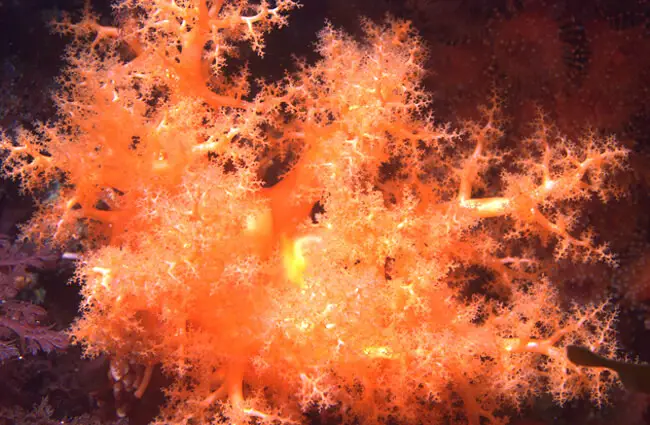

A World of Shapes and Sizes

The diversity within the sea cucumber family is astonishing. There are over 1,700 known species, ranging dramatically in size from tiny, inch-long specimens to giants stretching over three meters (ten feet) in length. Their coloration is equally varied, displaying hues of black, brown, green, red, and even brilliant white or iridescent patterns. Some species are sleek and smooth, while others are covered in elaborate papillae or spiny projections, each adaptation suited to its specific habitat and lifestyle.

Where Do Sea Cucumbers Live? Unveiling Their Habitats

Global Distribution

Sea cucumbers are true cosmopolitans of the ocean, inhabiting every marine environment imaginable. Their global distribution spans all the world’s oceans, from the frigid waters of the poles to the warm, tropical seas of the equator. They can be found in virtually every depth zone, from the intertidal splash zone where they might be exposed at low tide, down to the crushing pressures of the deepest oceanic trenches, such as the Mariana Trench.

Preferred Environments

While widespread, different species have distinct preferences. Many thrive in shallow coastal waters, nestled among coral reefs, seagrass beds, or rocky crevices. Here, they often blend seamlessly with their surroundings, camouflaged against the substrate. Other species are masters of the soft sediment, burrowing into sandy or muddy bottoms, with only their feeding tentacles exposed. The deep sea is also a stronghold for sea cucumbers, where they often dominate the seafloor biomass, slowly traversing the abyssal plains in search of detritus. For an animal lover hoping to spot one, shallow, calm waters with sandy or rocky bottoms are often the best bet, particularly during low tide or while snorkeling in tropical regions. Remember to observe them from a distance and avoid disturbing their natural behavior.

A Glimpse into the Past: Sea Cucumber Evolution

The evolutionary journey of sea cucumbers is a testament to their resilience and adaptability. Fossil records indicate that holothurians have existed for at least 400 million years, with some estimates pushing their origins back to the Ordovician period. Their soft bodies, however, do not lend themselves well to fossilization, making their early history somewhat elusive. Despite this, the discovery of ancient ossicles (microscopic skeletal elements) provides clues to their lineage. Over millions of years, they have evolved a remarkable array of adaptations, from their unique feeding strategies to their extraordinary defensive mechanisms, allowing them to thrive in diverse and often challenging marine environments. Their persistence through multiple mass extinction events underscores their evolutionary success.

The Ocean’s Clean-Up Crew: What Do Sea Cucumbers Eat?

Detritivores Extraordinaire

Sea cucumbers are the unsung heroes of marine ecosystems, primarily functioning as detritivores. This means their diet consists mainly of detritus: decaying organic matter, microscopic algae, bacteria, and other tiny organisms found in the sediment or suspended in the water column. They are essentially the ocean’s vacuum cleaners, playing a crucial role in nutrient cycling and sediment bioturbation. By ingesting vast quantities of seafloor sediment, they process organic material, release nutrients back into the water, and prevent the accumulation of organic waste, which could otherwise lead to anoxic conditions.

Feeding Mechanisms

Their feeding methods vary depending on the species. Most sea cucumbers are deposit feeders, using specialized, often branched or feathery, tentacles that surround their mouth. These tentacles are coated in mucus, which traps food particles as they are swept across the seafloor or extended into the water. The tentacles are then retracted one by one into the mouth, where the food is scraped off. Other species are filter feeders, extending their tentacles into the water column to capture suspended plankton and organic particles. This continuous processing of sediment and water makes them indispensable for maintaining healthy marine environments.

The Dance of Life: Mating and Reproduction

Sexual Reproduction

The majority of sea cucumbers reproduce sexually, typically through external fertilization. Most species are dioecious, meaning individuals are either male or female, though some are hermaphroditic. During spawning events, which are often synchronized with lunar cycles or specific environmental cues, males and females release their gametes (sperm and eggs) directly into the water column. This mass spawning increases the chances of successful fertilization. The fertilized eggs develop into free-swimming larval stages, which drift as plankton for a period before settling on the seafloor and metamorphosing into juvenile sea cucumbers. This pelagic larval stage aids in dispersal, allowing sea cucumbers to colonize new areas.

Asexual Reproduction

Beyond sexual reproduction, many sea cucumber species exhibit remarkable abilities for asexual reproduction. Fission, where an individual spontaneously divides itself into two or more pieces, is common. Each piece then regenerates into a complete, genetically identical individual. This incredible regenerative capacity also plays a role in their survival after injury or predation.

Ecosystem Engineers: Sea Cucumbers’ Role in the Marine World

Sediment Bioturbation

The ecological contributions of sea cucumbers are vast and often underestimated. As deposit feeders, they constantly churn and aerate the seafloor sediments, a process known as bioturbation. This activity is vital for the health of marine ecosystems. It prevents the build-up of anoxic layers, facilitates the breakdown of organic matter, and releases essential nutrients back into the water column, making them available for other organisms. Essentially, they are the ocean’s plows, tilling the seabed and promoting biodiversity.

Food Source and Shelter

While their primary defense mechanisms deter many predators, sea cucumbers do serve as a food source for certain fish, crabs, and sea stars. More intriguingly, some species engage in fascinating symbiotic relationships. Perhaps the most famous is the pearlfish, which often seeks refuge within the sea cucumber’s cloaca (its posterior opening). The pearlfish gains protection from predators, and in some cases, may even feed on the sea cucumber’s gonads or respiratory trees, making it a commensal or parasitic relationship depending on the species involved. This interaction highlights the complex web of life in which sea cucumbers are intricately woven.

Sea Cucumbers and Humanity: A Complex Relationship

Culinary Delicacy and Traditional Medicine

For centuries, sea cucumbers have held significant cultural and economic importance, particularly in East Asian cuisines and traditional medicine. Known as “trepang” or “bêche-de-mer,” they are considered a delicacy and are prized for their unique texture and perceived health benefits. They are often dried and rehydrated for use in soups, stews, and stir-fries. In traditional medicine, extracts from sea cucumbers are believed to possess anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and wound-healing properties, leading to extensive research into their bioactive compounds.

Conservation Concerns

Unfortunately, the high demand for sea cucumbers has led to severe overharvesting in many parts of the world. Slow growth rates, late maturity, and localized spawning make many species particularly vulnerable to depletion. This overexploitation not only threatens sea cucumber populations but also has cascading negative impacts on the marine ecosystems they help maintain. Conservation efforts, including fishing quotas, protected areas, and aquaculture initiatives, are crucial to ensuring the sustainability of these vital creatures. Aspiring zoologists should be aware of these conservation challenges and the role scientific research plays in informing sustainable management practices.

Encountering Sea Cucumbers in the Wild

For hikers or beachcombers who might encounter a sea cucumber washed ashore or in a shallow tide pool, the best course of action is simple: observe, but do not disturb. These animals are harmless to humans, but handling them can cause stress and potentially trigger their defensive mechanisms, such as evisceration, which can be energetically costly for the animal. If found stranded, gently return it to the water if possible, ensuring it is placed in a calm area away from strong currents or direct sunlight. Always prioritize the animal’s well-being and respect its natural habitat.

Fascinating Facts and Unique Adaptations

- Evisceration: When severely stressed or threatened, many sea cucumbers can expel their internal organs (digestive tract, respiratory trees, gonads) through their anus or mouth. This startling defense mechanism can distract or entangle a predator, allowing the sea cucumber to escape. Remarkably, they can regenerate all lost organs within weeks or months.

- Cuvierian Tubules: Some species possess sticky, often toxic, white threads called Cuvierian tubules, which are expelled from the anus when threatened. These tubules can entangle and incapacitate predators, acting like a natural superglue.

- Respiratory Trees: Unlike most echinoderms, sea cucumbers breathe through a unique pair of “respiratory trees” located internally near the cloaca. They draw water in through the anus and pump it through these branched structures, where oxygen exchange occurs.

- Mutable Collagenous Tissue (MCT): One of their most extraordinary adaptations is their mutable collagenous tissue. This specialized connective tissue allows them to rapidly change the rigidity of their body wall. They can become incredibly soft and pliable to squeeze through tight spaces, or stiffen their bodies to become rigid and unpalatable to predators.

- No Brain, But a Nerve Ring: Despite lacking a centralized brain, sea cucumbers possess a nerve ring around their mouth and radial nerves extending throughout their body, allowing for coordinated movement and responses to stimuli.

- Water Vascular System: Like other echinoderms, they utilize a water vascular system to operate their tube feet and tentacles, using hydraulic pressure for locomotion and feeding.

Caring for Sea Cucumbers in Captivity: A Zookeeper’s Guide

For zookeepers or aquarists caring for sea cucumbers, understanding their specific needs is paramount to their well-being. These animals, while seemingly robust, require careful attention to their environment and diet.

Habitat Requirements

- Substrate: Provide a deep, soft sand or fine gravel substrate, especially for burrowing species. This allows them to exhibit natural behaviors like sifting and hiding.

- Water Quality: Maintain pristine water conditions. Sea cucumbers are sensitive to nitrates and ammonia. Regular water changes and robust filtration are essential.

- Temperature and Salinity: Replicate the natural temperature and salinity of their native habitat. Tropical species require warmer waters (e.g., 24-28°C or 75-82°F) and stable salinity (e.g., 1.023-1.025 specific gravity).

- Tank Size: Ensure adequate tank size to prevent overcrowding and allow for sufficient foraging area.

Diet and Feeding

- Detritus and Specialized Foods: As detritivores, their primary diet should consist of fine organic detritus. Supplement with commercially available invertebrate foods, spirulina powder, or finely crushed flakes.

- Avoiding Overfeeding: While they are constant feeders, overfeeding can foul the water. Provide small, frequent feedings or ensure a healthy biofilm and detritus layer in the tank.

Health Monitoring and Common Issues

- Signs of Stress: Look for changes in behavior, such as prolonged inactivity, refusal to feed, or unusual body posture. Discoloration or lesions can indicate disease.

- Regeneration Capabilities: Be aware that minor injuries are often regenerated. However, severe evisceration in captivity can be a sign of extreme stress and may require isolation and careful monitoring.

What to Avoid

- Sudden Environmental Changes: Avoid abrupt shifts in temperature, salinity, or water chemistry, as these can be highly stressful.

- Incompatible Tank Mates: Do not house sea cucumbers with aggressive fish or invertebrates that might nip at them or attempt to eat them. Also, be cautious with species that might be affected by the toxins released during evisceration.

- Handling Stress: Minimize handling. If handling is necessary, do so gently and support the entire body to prevent tearing or damage.

- Toxins from Evisceration: Be aware that some species release holothurin, a potent toxin, when eviscerating. If a sea cucumber eviscerates in a closed system, it may be necessary to perform a large water change and remove the expelled organs to prevent harm to other tank inhabitants.

Conclusion: Appreciating the Humble Sea Cucumber

From their ancient origins to their vital role in maintaining the health of our oceans, sea cucumbers are truly remarkable creatures. Their unique biology, bizarre defense mechanisms, and quiet dedication to cleaning the seafloor make them deserving of our attention and respect. As we continue to explore and understand the intricate web of marine life, the humble sea cucumber stands as a powerful reminder of the importance of every organism, no matter how unassuming, in the grand tapestry of our planet’s ecosystems. Protecting these ocean engineers is not just about saving a species; it is about safeguarding the health and future of the marine world for generations to come.

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-100x75.jpg)