The Gentle Giant of the Deep: Unveiling the Mysteries of the Whale Shark

Beneath the shimmering surface of our planet’s vast oceans swims a creature of immense proportions and surprising grace: the Whale Shark. Far from the fearsome predators often associated with its name, this magnificent animal is a true gentle giant, captivating scientists, divers, and ocean enthusiasts alike with its serene presence and unique lifestyle. As the largest fish in the world, the Whale Shark, scientifically known as Rhincodon typus, offers a window into the wonders of marine biology and the intricate balance of our global ecosystems.

A Colossal Canvas: Appearance and Basic Biology

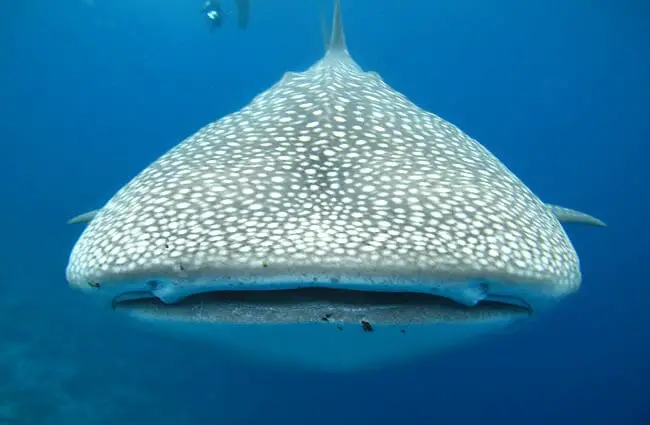

Imagine a fish the size of a school bus, adorned with a mesmerizing pattern of white spots and stripes against a dark grey or brownish-blue background. This is the Whale Shark. Its colossal body can reach lengths exceeding 18 meters (60 feet) and weigh over 21.5 metric tons (47,000 pounds), making it an undisputed heavyweight champion of the aquatic world. Despite its immense size, its streamlined body, broad, flattened head, and distinctive wide mouth give it an almost benevolent appearance. Five large gill slits on each side of its head are a clear indicator of its cartilaginous fish lineage, a characteristic shared with other sharks and rays.

Wandering Waters: Habitat and Distribution

The Whale Shark is a truly cosmopolitan traveler, preferring the warm, tropical, and warm-temperate waters of the world’s oceans. Its distribution spans the globe, from the Atlantic to the Pacific and Indian Oceans, typically found between 30°N and 30°S latitudes. These majestic creatures are primarily pelagic, meaning they inhabit the open ocean, but they are also known to aggregate in coastal areas with abundant food sources. Key aggregation sites, where hundreds of individuals can be observed, include the waters off the Philippines, Mexico (Yucatan Peninsula), Australia (Ningaloo Reef), Indonesia, and the Galapagos Islands. These aggregations are often seasonal, coinciding with plankton blooms or fish spawning events, highlighting their migratory nature in search of sustenance.

The Ultimate Filter Feeder: What’s on the Menu?

Despite its shark classification, the Whale Shark is not a hunter of large prey. Instead, it is a highly specialized filter feeder, a dietary strategy more commonly associated with baleen whales. Its enormous mouth, which can open up to 1.5 meters (5 feet) wide, acts like a massive sieve. As it cruises slowly through the water, it gulps in vast quantities of water containing its primary diet: plankton, including copepods, krill, and fish eggs. Small fish and squid are also opportunistically consumed. The water is then expelled through its gill slits, while specialized dermal denticles and gill rakers trap the tiny food particles, which are then swallowed. This efficient feeding mechanism allows the Whale Shark to thrive on microscopic organisms, sustaining its enormous body mass.

A Glimpse into the Past: Evolutionary History

The evolutionary journey of the Whale Shark is a testament to the enduring success of cartilaginous fish. As a member of the class Chondrichthyes, its lineage stretches back hundreds of millions of years, predating most bony fish and all land vertebrates. While specific fossil records for Rhincodon typus are scarce, its general morphology and filter-feeding adaptation suggest a long evolutionary history of specialization. It represents a remarkable example of convergent evolution with baleen whales, where two distantly related groups developed similar feeding strategies to exploit abundant planktonic resources in the ocean.

The Circle of Life: Mating and Reproduction

The reproductive biology of the Whale Shark remained largely a mystery for many years, a challenge given their elusive nature and vast oceanic habitat. However, scientific observations have revealed that Whale Sharks are ovoviviparous. This means that while they produce eggs, these eggs hatch internally within the mother’s uterus, and the young are born live. A single pregnant female can carry a remarkably large litter, potentially hundreds of pups, though not all may survive to birth. The pups are born relatively large, around 40 to 60 centimeters (16 to 24 inches) long, giving them a better chance of survival in the open ocean. Growth rates are slow, and Whale Sharks are thought to reach sexual maturity at around 30 years of age, with a lifespan estimated to be between 70 and 100 years, or even longer.

Ecosystem Engineer: Role and Interactions

As the largest filter feeder, the Whale Shark plays a significant role in its marine ecosystem. By consuming vast quantities of plankton, it helps regulate plankton populations and contributes to nutrient cycling within the water column. Its sheer size and migratory patterns also mean it can transport nutrients across vast distances. Due to its enormous size, adult Whale Sharks have very few natural predators, primarily limited to large marine predators like orcas or great white sharks, though attacks are rare. Juveniles, however, may be more vulnerable. Whale Sharks often share their feeding grounds with other marine life, including schools of fish, manta rays, and various species of sharks, creating vibrant and biodiverse ecosystems.

Human Connections: Interaction and Cultural Significance

The Whale Shark’s docile nature has fostered a unique relationship with humans. Unlike many other large sharks, they pose no threat to people and are often sought out for ecotourism experiences. Swimming alongside these magnificent creatures has become a popular and often life-changing activity, generating significant economic benefits for local communities in areas where they aggregate. This interaction has also elevated the Whale Shark to an iconic status, symbolizing the beauty and fragility of marine life and inspiring conservation efforts worldwide. In some cultures, they are revered and seen as guardians of the ocean.

Conservation Concerns: Threats and Protection

Despite their iconic status, Whale Sharks face significant threats, leading to their classification as an Endangered species by the IUCN. The primary dangers include:

- Targeted Fisheries: Historically, Whale Sharks were hunted for their meat, fins, and oil in certain regions.

- Bycatch: They are often caught unintentionally in fishing gear targeting other species.

- Vessel Strikes: Collisions with large ships can cause serious injury or death.

- Plastic Pollution: Ingesting microplastics and other debris can be harmful.

- Habitat Degradation: Pollution and climate change impact their food sources and habitats.

- Unregulated Tourism: Poorly managed tourism can disturb feeding patterns and stress individuals.

International agreements and national laws are in place to protect Whale Sharks, and responsible ecotourism operators play a crucial role in funding research and conservation initiatives.

Diving Deeper: Practical Insights and Expert Knowledge

Finding the Gentle Giant: Where and How to Encounter a Whale Shark

For the dedicated animal lover or aspiring zoologist hoping to observe Whale Sharks in their natural habitat, careful planning is key. These are some of the most reliable locations and times:

- Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia: March to July, coinciding with coral spawning.

- Isla Holbox and Isla Mujeres, Mexico: May to September, during plankton blooms and fish spawning.

- Donsol and Oslob, Philippines: Donsol (December to May) offers more regulated, ethical encounters. Oslob is controversial due to feeding practices.

- Galapagos Islands, Ecuador: June to December, particularly around Darwin and Wolf Islands.

- Tofo Beach, Mozambique: October to March.

- Maldives: Year-round sightings are possible, but particularly good in the South Ari Atoll.

To maximize your chances, research local tour operators with strong ethical guidelines and conservation commitments. Look for tours that emphasize passive observation, maintaining respectful distances, and avoiding any disturbance to the animals.

Encountering a Whale Shark in the Wild: What to Do

Should you be fortunate enough to encounter a Whale Shark while swimming, snorkeling, or diving, remember these guidelines to ensure a safe and respectful interaction:

- Maintain Distance: Always keep a respectful distance, typically 3-4 meters (10-13 feet) from the body and 4-5 meters (13-16 feet) from the tail.

- No Touching: Never attempt to touch, ride, or harass a Whale Shark. This can stress the animal, remove its protective mucous layer, and is often illegal.

- Swim Calmly: Move slowly and calmly. Avoid sudden movements or loud noises that might startle the shark.

- Observe, Do Not Pursue: Allow the shark to approach or swim past you. Do not chase it or block its path.

- Limit Group Size: If part of a tour, adhere to group size limits to minimize impact.

- No Flash Photography: Avoid using flash photography, which can disorient marine life.

Your actions contribute directly to the well-being of these magnificent creatures and the sustainability of ecotourism.

Caring for a Whale Shark in Captivity: A Zookeeper’s Perspective

Keeping Whale Sharks in captivity is an immense undertaking, requiring highly specialized facilities and expertise. While most conservation efforts focus on protecting them in the wild, a few aquariums worldwide have housed Whale Sharks, primarily for research and public education. For a zookeeper, the tasks are rigorous and demanding:

- Enclosure Design: Providing an enormous tank, often millions of gallons, with complex filtration and water circulation systems to mimic oceanic conditions.

- Dietary Management: Replicating their natural diet of plankton, krill, and small fish. This involves culturing or sourcing vast quantities of live or frozen food, often supplemented with vitamins.

- Water Quality: Meticulous monitoring and maintenance of water parameters (temperature, salinity, pH, oxygen levels, nitrogenous waste) to ensure optimal health.

- Health Monitoring: Regular veterinary checks, including blood sampling, visual inspections, and behavioral observations to detect any signs of illness or stress.

- Enrichment: While less complex than for terrestrial animals, providing a stimulating environment, such as varied water currents, can be important.

- Research and Education: Participating in scientific studies and educating the public about Whale Shark biology and conservation.

Tasks to be avoided:

- Housing in tanks that are too small, leading to stress and physical injury.

- Feeding an improper or insufficient diet.

- Introducing incompatible tank mates that could cause stress or injury.

- Any practices that compromise the animal’s welfare for public display.

The ethical implications of keeping such large, migratory animals in captivity are a subject of ongoing debate within the zoological community.

A Huge List of Interesting Facts About Whale Sharks

- The Whale Shark has approximately 300 rows of tiny teeth, but they are not used for biting or chewing. They are vestigial, meaning they are remnants of an evolutionary past.

- Each Whale Shark possesses a unique pattern of spots, much like a human fingerprint. This allows researchers to identify individual sharks for tracking and population studies.

- They have a thick skin, up to 10 centimeters (4 inches) thick, providing protection against predators and environmental factors.

- Whale Sharks are known to perform “vertical feeding,” where they position themselves vertically in the water column with their mouths open, gulping plankton near the surface.

- Despite their size, they are surprisingly agile and can dive to depths of over 1,000 meters (3,280 feet).

- Their eyes are relatively small for their head size and are located on the sides of their flat heads.

- The name “Whale Shark” comes from its size, which rivals that of whales, and its filter-feeding diet, combined with its classification as a shark.

- They are solitary creatures for much of their lives, only congregating in large numbers at specific feeding grounds.

- The largest confirmed Whale Shark measured 18.8 meters (61.7 feet) in length.

- Whale Sharks have a unique ability to “cough” or “sneeze” to clear their gill rakers of unwanted debris.

The Future of the Gentle Giant

The Whale Shark stands as a magnificent emblem of ocean health and biodiversity. Its sheer size, gentle demeanor, and unique feeding strategy make it one of the most fascinating creatures on Earth. From the student researching its intricate biology to the diver experiencing its serene presence, the Whale Shark inspires awe and a profound sense of connection to the marine world. Protecting this endangered species requires a global commitment to sustainable fishing practices, combating pollution, mitigating climate change, and promoting responsible tourism. By understanding and respecting the gentle giant of the deep, humanity can ensure that future generations will also have the privilege of sharing our oceans with the incredible Whale Shark.

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-238x178.jpg)

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-100x75.jpg)