Introducing the Flying Dragon

Often referred to as the “Flying Dragon,” Draco volans is a captivating lizard species native to Southeast Asia. Despite the evocative name, this remarkable reptile does not truly fly; it glides skillfully through the forest canopy. This ability, combined with its unique appearance, has cemented its place in local folklore and captured the imagination of naturalists for generations. The “flying” aspect is not achieved through wings but through specialized patagial folds (extended ribs covered with skin) that allow it to launch into the air and glide for considerable distances.

Habitat and Distribution

The Flying Dragon’s range extends throughout Southeast Asia, encompassing countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines. These lizards are arboreal, meaning they spend almost their entire lives in trees. Their preferred habitat is dense primary and secondary rainforest, where they thrive among the high canopy. They are typically found at elevations below 1,000 meters, though variations exist across different regions. The availability of suitable trees with ample foliage for gliding and foraging is crucial to their survival. They require a warm and humid climate to remain active and maintain their physiological functions.

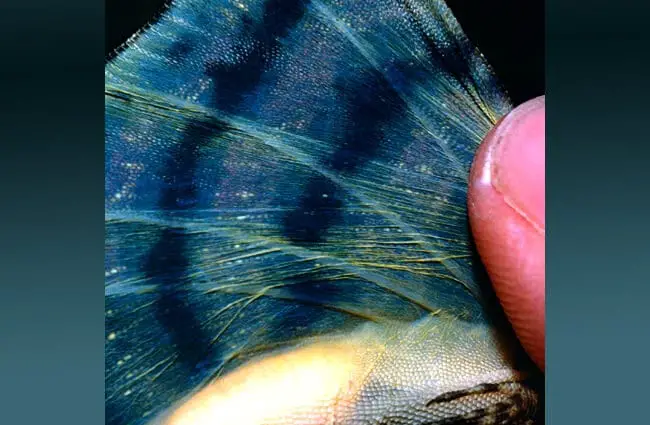

Physical Characteristics

Adult Flying Dragons typically reach a total length of 20 to 24 centimeters, with males often being slightly larger and more brightly colored than females. Their most defining feature is, of course, the patagium. These extended ribs covered with skin dramatically increase their surface area, allowing them to glide efficiently. The patagium is usually a muted green or brown, providing camouflage among the leaves. Their bodies are slender and agile, perfectly adapted for navigating the complex forest canopy. They possess sharp claws that enable them to grip onto branches securely. Their color can also change to match the surrounding vegetation.

Gliding Mechanics and Behavior

Contrary to popular belief, Flying Dragons do not simply leap and hope for the best. They are surprisingly adept gliders. They launch themselves from elevated branches, extending their patagium and using their flattened bodies to create lift. They can control their direction and glide angle by subtly adjusting the shape of their patagium and using their tail as a rudder. Glides can cover distances of up to 60 meters, allowing them to move between trees efficiently and escape predators. They often glide downwards at a shallow angle, conserving energy. While gliding, they appear to “fly” gracefully.

Diet and Foraging

Flying Dragons are primarily insectivores, with ants making up a significant portion of their diet. They also consume termites, beetles, and other small invertebrates. Their foraging strategy involves actively searching for prey on tree trunks and branches. They are opportunistic feeders, meaning they will take advantage of whatever food source is readily available. They possess a relatively simple digestive system, adapted for processing insect-based meals. They are also fond of eggs of other insects.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The mating season for Flying Dragons typically occurs during the wet season. Males will engage in elaborate displays to attract females, including head-bobbing and dewlap extensions. After mating, the female will lay a small clutch of eggs, usually two to five, in a concealed nest within tree cavities or under loose bark. The eggs are relatively soft shelled and take approximately 45 to 60 days to hatch. Young Flying Dragons are miniature versions of their parents and are capable of gliding shortly after hatching. They reach sexual maturity within one to two years.

Ecological Role and Interactions

Flying Dragons play an important role in the rainforest ecosystem. As insectivores, they help to control populations of various insect species. They are also prey for larger predators, such as snakes, birds of prey, and mammals. Their gliding behavior may contribute to seed dispersal, as they inadvertently carry seeds on their bodies. They coexist with other arboreal lizards, competing for resources and space. They generally do not engage in aggressive behaviors toward other species.

Flying Dragons and Human Interactions

While not typically considered a threat to humans, Flying Dragons are sometimes caught and sold as exotic pets. However, their specialized dietary needs and arboreal lifestyle make them difficult to care for in captivity. Habitat loss due to deforestation poses the greatest threat to their populations. Local communities often hold these lizards in high regard, associating them with good luck and prosperity. Their unique gliding abilities have also inspired various artistic and cultural representations.

Conservation Status

The conservation status of Flying Dragons varies depending on the specific species and geographic location. Some populations are relatively stable, while others are declining due to habitat loss and degradation. Deforestation, particularly the conversion of rainforest to agricultural land, is the primary threat. Conservation efforts focus on protecting and restoring rainforest habitat, as well as promoting sustainable land-use practices. Raising awareness about the importance of these unique lizards is also crucial.

Interesting Facts

- Flying Dragons are also known as “gliding lizards” or “flying lizards”.

- Their patagium is not supported by the forelimbs but by elongated ribs.

- They can change the color of their skin to blend in with their surroundings.

- Males are typically more brightly colored than females.

- They are most active during the day.

- They can survive for extended periods without drinking water, obtaining moisture from their food.

- Their gliding ability is a form of arboreal locomotion, allowing them to navigate the forest canopy efficiently.

For the Aspiring Zoologist: Deeper Dive

The evolutionary origins of the patagium are a fascinating area of study. While the exact mechanisms are still being investigated, it is believed to have evolved from elongated ribs that initially served as a form of display or thermoregulation. Over time, these ribs became covered with skin, increasing their surface area and eventually enabling gliding. Phylogenetic analyses suggest that Flying Dragons are closely related to other agamid lizards but exhibit unique adaptations for arboreal life. Further research is needed to fully understand the genetic and developmental basis of their gliding ability.

Encountering a Flying Dragon in the Wild

If you are fortunate enough to encounter a Flying Dragon in the wild, observe it from a respectful distance. Avoid disturbing its habitat or attempting to handle it. These lizards are generally shy and will quickly retreat if approached. Appreciate its unique beauty and play a role in protecting its habitat.

Caring for Flying Dragons in Captivity

Keeping Flying Dragons in captivity is challenging due to their specialized needs. They require a large, arboreal enclosure with plenty of branches, foliage, and basking spots. Their diet should consist primarily of live insects, supplemented with vitamins and minerals. Maintaining appropriate temperature and humidity levels is crucial. It is essential to provide them with ample space to glide and exercise. Careful monitoring of their health and behavior is also necessary.

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-238x178.jpg)

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-100x75.jpg)