The Lost Giants of New Zealand: A Deep Dive into the World of Moa

For centuries, Māori legends spoke of towering birds, flightless and formidable. These were not myths, but memories of the moa, a unique group of birds that once dominated the landscape of New Zealand. Now extinct, the moa represents a fascinating story of evolution, adaptation, and ultimately, vulnerability. This article explores the world of these lost giants, from their habitat and diet to their interaction with humans and their place in the ecosystem.

What Were Moa?

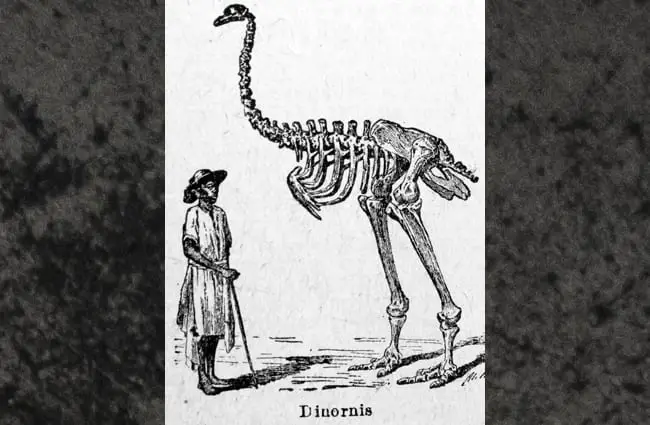

Moa comprised nine species of flightless birds that were endemic to New Zealand. They were distinguished by their large size, powerful legs, and absence of wings. The name “moa” refers to the entire group, not a single species. Size ranged from the little bush moa, about 1.2 metres tall, to the giant moa, which could reach over 3.6 metres and weigh up to 250 kilograms. Imagine an ostrich, but even larger and more robust.

Habitat and Distribution

Before humans arrived, moa flourished across a wide variety of habitats, from dense forests and scrublands to alpine regions and even coastal areas. Different species specialised in different environments. For example, the heavy footed moa inhabited the warmer, wetter forests of the North Island, while the stout legged moa preferred the tussock grasslands of the South Island. Their widespread distribution highlights their adaptability and ecological importance.

Evolutionary History

Moa are believed to have descended from a lineage of flightless birds that arrived in New Zealand from elsewhere around 70-80 million years ago. In the absence of mammalian predators, they evolved a remarkable transformation: wings became vestigial, bodies grew larger, and legs became powerful, enabling them to thrive in a unique ecological niche. They belong to the ratite family, which includes ostriches, emus, and kiwis, all sharing a common flightless ancestor. Fossil evidence shows that moa had been evolving in New Zealand for millions of years, giving rise to the diverse range of species we know today.

Diet and Feeding Habits

Moa were herbivores that fed mainly on leaves, twigs, fruits, and seeds. Their digestive systems were adapted to process tough plant material, aided by gastroliths—stones swallowed to help grind food in the gizzard. Evidence from coprolites—fossilised droppings—shows that different species had specialised diets. Some preferred browsing on low lying vegetation, while others could reach higher branches. Their feeding habits played a crucial role in shaping the vegetation structure of New Zealand’s ecosystems.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Moa laid large, pear shaped eggs, some over 30 centimetres long and weighing up to 8 kilograms. These eggs were typically laid in nests on the ground, often concealed in vegetation. The young were precocial, meaning they were relatively independent and capable of foraging shortly after hatching. Little is known about their lifespan, but they could live at least 20 years. The large size of their eggs suggests a relatively slow reproductive rate, making them vulnerable to population decline.

Moa and the Ecosystem

Moa were a keystone species in New Zealand’s ecosystems. As large herbivores, they shaped vegetation structure and influenced the distribution of other species. Their foraging created gaps in the forest canopy, allowing sunlight to reach the forest floor and promoting the growth of new plants. They also served as a food source for predators, most notably the giant Haast’s eagle, one of the largest raptors ever to exist. The extinction of moa had cascading effects on the entire ecosystem, altering plant communities and impacting the populations of other animals.

Human Interaction and Extinction

The arrival of Māori settlers in New Zealand around 1300 AD marked a turning point in the history of moa. Māori hunted moa for food using spears, snares, and other trapping techniques. Archaeological evidence shows that moa were a significant part of the Māori diet for several centuries. However, the rate of hunting, combined with habitat destruction through deforestation, ultimately led to the extinction of all moa species by around 1400 AD. This extinction is one of the most well documented examples of human caused extinction.

Interesting Facts About Moa

- Moa bones are often found in Māori middens, ancient refuse heaps, providing valuable insights into their hunting practices.

- Scientists can determine the diet of moa by analysing the contents of their coprolites.

- Some moa species had brightly coloured feathers, as indicated by preserved feather fragments, suggesting that some species had colourful plumage.

- The giant moa was one of the tallest bird species ever to exist.

- Moa bones have been used by archaeologists to date early Māori settlements.

- The name “moa” comes from the Māori word for “bird”.

What if You Encountered a Moa Today? (A Hypothetical Scenario)

Of course, encountering a moa today is impossible. However, if one were to miraculously reappear, it would be a significant event. Moa were likely wary of humans, so approaching one would be difficult. It is crucial to observe from a distance and avoid disturbing its natural behaviour. Reporting the sighting to wildlife authorities would be essential for conservation efforts.

For the Aspiring Zoologist

Research into moa continues today, using ancient DNA analysis, skeletal morphology, and ecological modelling. Active research areas include understanding the genetic diversity of moa populations, reconstructing their evolutionary relationships, and investigating the causes of their extinction. The study of moa provides valuable lessons about the impact of human activities on ecosystems and the importance of conservation.

For the Zookeeper

While currently extinct, if one were tasked with caring for a hypothetical moa, the focus would be on providing a large, naturalistic enclosure with a varied diet of leaves, fruits, and seeds. Socialisation would be important, potentially pairing individuals to encourage breeding. Careful monitoring of health and behaviour would be essential. Enrichment activities, such as providing foraging opportunities, would be crucial to stimulate their natural instincts.

The story of the moa is a poignant reminder of the fragility of life and the consequences of human actions. While these magnificent birds are gone, their legacy continues to inspire scientists, conservationists, and anyone fascinated by the natural world. Their story serves as a powerful call to protect the biodiversity of our planet before it’s too late.

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-238x178.jpg)

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-100x75.jpg)