The Enigmatic World of Jellyfish: Ancient Mariners of the Deep

Drifting through the ocean’s currents, these ethereal creatures have captivated human imagination for millennia. Jellyfish, with their pulsating bells and trailing tentacles, are far more than simple blobs of gelatinous tissue. They represent one of Earth’s oldest and most successful animal lineages, embodying a profound simplicity that belies their ecological significance and biological complexity. From the sunlit surface waters to the abyssal depths, these mesmerizing invertebrates play crucial roles in marine ecosystems, inspiring awe, scientific inquiry, and sometimes, a healthy dose of caution.

What Exactly is a Jellyfish?

At its core, a jellyfish is a free-swimming marine animal belonging to the phylum Cnidaria, a group that also includes corals and sea anemones. The most recognizable form of a jellyfish is the medusa stage, characterized by its bell-shaped body and trailing tentacles. Despite their often-complex appearance, jellyfish possess a remarkably simple anatomy. They lack a brain, heart, bones, and even a respiratory system. Their bodies are composed of over 95% water, with a jelly-like substance called mesoglea providing structural support. Nerve nets allow them to sense their environment and coordinate movement, while specialized stinging cells, called nematocysts, arm their tentacles for defense and prey capture. This ancient body plan has allowed them to thrive in virtually every marine environment on Earth.

A Glimpse into Ancient History: The Evolutionary Journey

Jellyfish are true living fossils, boasting an evolutionary history stretching back at least 500 million years, possibly even 700 million years. This makes them among the oldest multicellular animals on the planet, predating dinosaurs, fish, and even most complex invertebrates. Their simple yet effective design has allowed them to survive multiple mass extinction events that wiped out countless other life forms. Fossil records, though rare due to their soft bodies, indicate that the basic jellyfish body plan has remained remarkably consistent over geological timescales. This incredible longevity highlights their adaptability and the success of their fundamental biological strategies, making them a fascinating subject for evolutionary biologists studying early animal life.

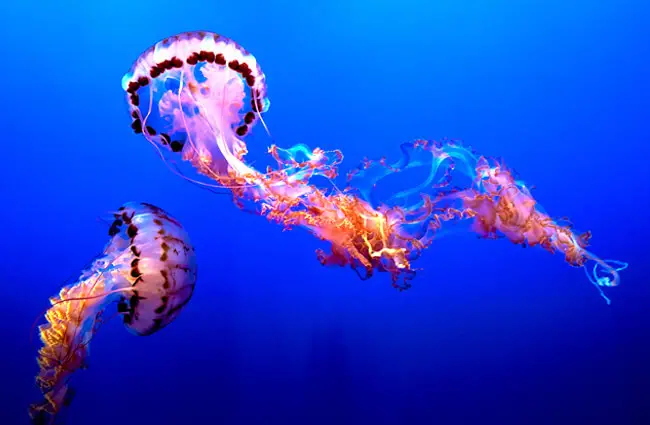

![Spectral jellyfish Photo by: Bernard Spragg. NZ [public domain] https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Jellyfish-1-650x425.jpg)

Where the Jellies Roam: Habitats and Distribution

The global distribution of jellyfish is vast, encompassing nearly every marine habitat imaginable. From the frigid waters of the Arctic and Antarctic to the warm, tropical seas, and from the sunlit surface to the crushing pressures of the deep ocean, jellyfish have found a niche. Most jellyfish are pelagic, meaning they live in the open ocean, drifting with currents. However, some species are benthic, spending part of their lives attached to the seafloor. While the vast majority are marine, a few species, such as the freshwater jellyfish (Craspedacusta sowerbii), have adapted to freshwater lakes and ponds, though these are relatively rare. Animal lovers hoping to spot jellyfish in the wild should look for coastal areas with calm waters, especially during warmer months when blooms are more common. Aquariums also offer excellent opportunities to observe these creatures in controlled environments.

The Art of Survival: Diet and Feeding Strategies

Jellyfish are primarily carnivorous predators, relying on their stinging tentacles to capture food. Their diet varies depending on species and size, but commonly includes zooplankton, small crustaceans, fish eggs and larvae, and even other jellyfish. The nematocysts on their tentacles are microscopic harpoons, injecting venom into prey to paralyze or kill it. Once subdued, the prey is moved to the mouth, located on the underside of the bell, and ingested into a central gastrovascular cavity where digestion occurs. This passive hunting strategy, where jellyfish drift and wait for prey to encounter their tentacles, is highly energy-efficient, allowing them to thrive in nutrient-poor waters. Some species, like the upside-down jellyfish (Cassiopea), even host symbiotic algae that photosynthesize, providing the jellyfish with additional nutrients.

The Dance of Life: Reproduction and Life Cycle

The life cycle of many jellyfish is a fascinating example of alternation of generations, involving both sexual and asexual reproduction. The most familiar stage is the free-swimming medusa, which is the sexually reproductive phase. Medusae release sperm and eggs into the water, where fertilization occurs, forming a larva called a planula. This planula eventually settles on a hard surface and develops into a sessile polyp. The polyp stage, often resembling a tiny sea anemone, can reproduce asexually by budding, creating more polyps. Under certain environmental conditions, these polyps undergo strobilation, a process where they bud off tiny, immature medusae called ephyrae. These ephyrae then grow into adult medusae, completing the cycle. This complex life history allows jellyfish to rapidly colonize new areas and adapt to changing conditions, contributing to their widespread success.

Jellyfish in the Web of Life: Ecosystem Roles and Interactions

Despite their simple appearance, jellyfish are integral components of marine ecosystems. They serve as both predators and prey, influencing food webs significantly. Large jellyfish can consume vast quantities of zooplankton and fish larvae, impacting populations of commercially important fish species. Conversely, jellyfish are a vital food source for a variety of marine animals, most notably sea turtles, ocean sunfish (mola mola), and some species of seabirds and fish. Some jellyfish also engage in symbiotic relationships, providing shelter for small fish and crustaceans among their tentacles, offering protection from predators in exchange for scraps of food or cleaning services. Their periodic population explosions, known as “blooms,” can dramatically alter local ecosystems, sometimes leading to cascading effects on other marine life.

Jellyfish and Humanity: From Inspiration to Interaction

Humanity’s interaction with jellyfish is multifaceted. Culturally, their otherworldly beauty has inspired art, literature, and even fashion. Their bioluminescent capabilities, where some species produce their own light, have led to groundbreaking scientific discoveries, particularly in genetic engineering with the isolation of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP). Economically, jellyfish can be a nuisance, clogging fishing nets, damaging aquaculture facilities, and impacting tourism through stings. However, in some cultures, particularly in Asia, jellyfish are harvested and consumed as a delicacy, valued for their unique texture and nutritional properties. Research into their unique biology continues to yield insights into aging, regeneration, and venom chemistry, with potential applications in medicine and biotechnology. The famous “immortal jellyfish,” Turritopsis dohrnii, capable of reverting to its polyp stage after reaching maturity, offers tantalizing clues about cellular regeneration.

Encountering Jellyfish in the Wild: Safety and Observation

For the animal lover or casual beachgoer, encountering a jellyfish can be a memorable experience. While many species are harmless or have mild stings, some, like the box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) found in Indo-Pacific waters, possess extremely potent venom that can be life-threatening. When observing jellyfish in their natural habitat, it is always best to maintain a respectful distance and avoid direct contact, even with seemingly dead jellyfish washed ashore, as nematocysts can remain active. If a sting occurs, immediate action is crucial:

- Rinse the affected area with seawater, not fresh water, as fresh water can trigger more nematocysts.

- Remove any visible tentacles carefully, perhaps with tweezers or a gloved hand.

- Apply vinegar (acetic acid) to the sting, if available, as it can help neutralize unfired nematocysts for many species, especially box jellyfish. However, for some species like the Portuguese Man O’ War, vinegar can worsen the sting. Hot water immersion (as hot as can be tolerated, around 45°C or 113°F) for 20-45 minutes can also help denature the venom and relieve pain.

- Seek medical attention if symptoms are severe, such as difficulty breathing, chest pain, or widespread rash.

Always research local jellyfish species and their associated risks before entering unfamiliar waters.

Caring for Captive Wonders: A Zookeeper’s Guide

Caring for jellyfish in captivity presents unique challenges and rewards. Zookeepers must meticulously replicate their natural environment to ensure their health and well-being. Key considerations include:

- Tank Design: Traditional rectangular tanks are unsuitable. Jellyfish require specialized “kreisel” or “plankton” tanks that create a gentle, circular current, preventing them from being pushed against tank walls or trapped in corners. These tanks eliminate sharp edges and provide continuous water flow.

- Water Quality: Pristine water quality is paramount. Stable salinity, temperature, pH, and low nutrient levels are critical. Advanced filtration systems, including protein skimmers and biological filters, are essential.

- Diet: Most captive jellyfish are fed live or frozen zooplankton, such as brine shrimp (Artemia) or rotifers. Feeding must be frequent and carefully monitored to prevent overfeeding, which can foul the water, or underfeeding, which leads to starvation.

- Handling: Jellyfish are extremely delicate. Direct handling should be avoided whenever possible. When transfer is necessary, specialized containers or gentle water flow techniques are used to minimize stress and physical damage.

- Environmental Enrichment: While jellyfish do not exhibit complex behaviors, maintaining appropriate light cycles and providing a stable, current-rich environment contributes to their overall health.

- Reproduction: Many species can be bred in captivity, requiring careful management of polyp colonies and environmental triggers for strobilation.

Avoid sudden changes in water parameters, aggressive tank mates, and any form of rough handling. A dedicated zookeeper’s attention to these details ensures these mesmerizing creatures can thrive and educate the public about the wonders of the ocean.

Fascinating Facts About Jellyfish

- No Brain, No Problem: Jellyfish navigate, hunt, and reproduce without a centralized brain. Their nerve net allows for complex actions.

- Mostly Water: A jellyfish’s body is typically over 95% water, making them incredibly efficient at buoyancy.

- Bioluminescent Wonders: Many deep-sea jellyfish produce their own light through bioluminescence, used for attracting prey, deterring predators, or communication.

- Size Extremes: Jellyfish range from tiny, almost microscopic species to the Lion’s Mane Jellyfish (Cyanea capillata), which can have tentacles over 120 feet (36 meters) long, longer than a blue whale.

- The Immortal Jellyfish: Turritopsis dohrnii has earned the nickname “immortal jellyfish” because it can revert to its juvenile polyp stage after reaching sexual maturity, theoretically allowing it to live indefinitely.

- Jellyfish Blooms: Under certain conditions, jellyfish populations can explode, forming massive “blooms” that can stretch for miles. These blooms are becoming more frequent, possibly due to climate change and overfishing of their predators.

- Ancient Eyes: Some jellyfish, particularly box jellyfish, possess complex eyes with lenses, corneas, and retinas, allowing them to detect light and even form images, despite lacking a centralized brain to process them.

Conclusion: Guardians of the Ocean’s Mysteries

Jellyfish, with their ancient lineage and alien beauty, are more than just a fleeting encounter at the beach. They are vital components of marine ecosystems, offering profound insights into evolution, biology, and the delicate balance of our oceans. From their intricate life cycles to their surprising intelligence without a brain, these gelatinous marvels continue to challenge our understanding of life itself. As we learn more about their resilience and adaptability, it becomes increasingly clear that appreciating and protecting these silent, pulsating guardians of the deep is essential for the health of our planet’s most expansive habitat.

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-100x75.jpg)