Beneath the shimmering surface of our planet’s oceans lies a world teeming with life, much of it familiar, some of it utterly alien. Among the most ancient and often overlooked inhabitants are the sea sponges. Far from being mere plants or inert rocks, these fascinating creatures represent some of the earliest forms of animal life, quietly performing vital roles in marine ecosystems across the globe. Prepare to dive deep into the intricate world of the sea sponge, an organism whose simple beauty belies its profound importance.

The Unsung Architects of the Ocean Floor: What is a Sea Sponge?

Often mistaken for plants or inanimate objects, sea sponges are, in fact, animals belonging to the phylum Porifera, a name derived from Latin meaning “pore-bearing.” These multicellular organisms are unique in their simplicity, lacking true tissues, organs, and a nervous system. Instead, their bodies are a marvel of cellular specialization, organized around a system of pores and canals that allow them to filter vast quantities of water. They are sessile, meaning they remain fixed in one place for their adult lives, typically attached to rocks, coral, or other hard substrates on the seafloor.

A Glimpse into Ancient Life: Evolutionary Journey

The evolutionary history of sea sponges is nothing short of remarkable. They are considered among the most primitive animals, with a lineage stretching back over 600 million years, predating the Cambrian explosion. Their simple body plan, characterized by a lack of complex organs, suggests they represent an early branch in the tree of animal life. Studying sponges provides invaluable insights into the origins of multicellularity and the fundamental processes that underpin animal biology. Their enduring presence across geological timescales is a testament to their evolutionary success and adaptability.

Home Sweet Home: Where Sea Sponges Thrive

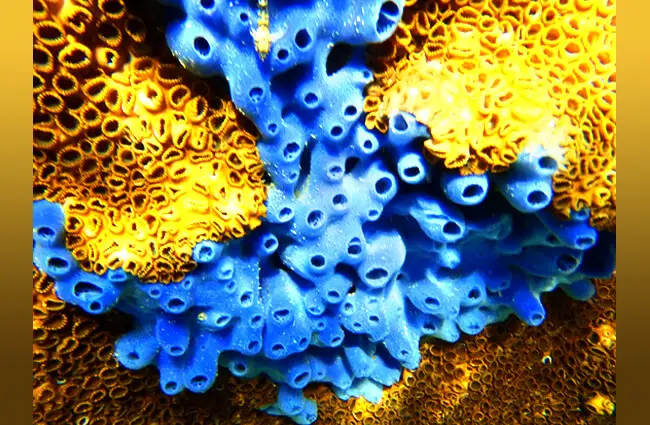

Sea sponges exhibit an astonishing diversity in form, size, and color, reflecting their adaptability to a wide range of marine environments. Their habitats are as varied as their appearances, making them a truly cosmopolitan group.

- Global Distribution: Sponges are found in all oceans, from the frigid polar waters to the warm tropics, and from shallow intertidal zones to the abyssal depths of the deep sea.

- Marine Dominance: The vast majority of sponge species are marine, inhabiting diverse substrates such as rocky reefs, coral reefs, sandy bottoms, and even mangrove roots.

- Freshwater Exceptions: While predominantly marine, a small but significant group of sponges, primarily from the family Spongillidae, has adapted to freshwater environments, thriving in lakes, rivers, and streams worldwide.

- Depth Adaptations: Some species are masters of the deep, enduring immense pressure and perpetual darkness, while others flourish in sunlit, nutrient-rich shallow waters.

Finding Sponges in the Wild: A Guide for Animal Lovers

For those eager to observe these ancient animals in their natural habitat, finding sea sponges can be a rewarding experience. They are often more common than one might expect, though their camouflage and sessile nature can make them blend seamlessly with their surroundings.

- Where to Look:

- Coral Reefs and Rocky Shores: These are prime locations. Sponges often attach to hard surfaces, crevices, and under ledges.

- Tide Pools: During low tide, some species can be found clinging to rocks in tide pools.

- Mangrove Roots: In tropical coastal areas, sponges frequently colonize the submerged roots of mangrove trees.

- Diving and Snorkeling: The best way to see a wide variety of sponges is by snorkeling or scuba diving in clear, healthy marine environments.

- How to Spot Them: Look for unusual textures, vibrant colors (reds, oranges, blues, purples), or distinct shapes (vase-like, encrusting, branching, fan-shaped) on rocks or coral. Remember, they do not move.

- Ethical Observation: Always observe sponges from a respectful distance. Avoid touching them, as this can damage their delicate structures and protective mucus layers. Never attempt to remove a sponge from its habitat.

The Ocean’s Natural Filters: How Sponges Eat

Sea sponges are quintessential filter feeders, playing a crucial role in maintaining water clarity and nutrient cycling. Their entire body plan is exquisitely designed for this purpose.

- Pore System: Water enters the sponge through thousands of tiny pores called ostia, covering its outer surface.

- Choanocytes: Inside the sponge, specialized cells called choanocytes, or “collar cells,” line internal chambers. Each choanocyte possesses a flagellum that beats rhythmically, creating a current that draws water through the sponge. The “collar” of microvilli around the flagellum traps microscopic food particles.

- Diet: Sponges primarily feed on bacteria, phytoplankton, small zooplankton, and organic detritus suspended in the water column.

- Osculum: After filtration, the filtered water, along with waste products, is expelled through one or more larger openings called oscula. A single sponge can filter thousands of liters of water per day, making them incredibly efficient biological purifiers.

The Cycle of Life: Sea Sponge Reproduction

Sponges exhibit remarkable versatility in their reproductive strategies, employing both asexual and sexual methods to ensure the continuation of their species.

- Asexual Reproduction:

- Budding: Small outgrowths, or buds, form on the parent sponge and eventually detach to grow into new, genetically identical individuals.

- Fragmentation: If a piece of a sponge breaks off, it can regenerate into a complete new sponge, provided the fragment is large enough and lands in a suitable environment. This incredible regenerative capacity is a hallmark of sponges.

- Gemmules: In some freshwater and a few marine species, sponges produce gemmules, which are dormant, resistant structures containing archaeocytes (totipotent cells). These gemmules can survive harsh conditions and later develop into new sponges when conditions improve.

- Sexual Reproduction:

- Hermaphroditism: Most sponges are hermaphroditic, meaning a single individual produces both sperm and eggs, though they typically do not self-fertilize.

- Broadcast Spawning: Many species release sperm into the water column, which is then carried by currents to other sponges.

- Internal Fertilization: Sperm entering another sponge is captured by choanocytes and transferred to eggs, which are often retained within the parent sponge.

- Larval Stage: Fertilized eggs develop into free-swimming larval forms, typically ciliated larvae, which disperse through the water column before settling on a suitable substrate and metamorphosing into a new sessile sponge. This larval stage is crucial for species dispersal and colonization of new areas.

More Than Just a Pore-Filled Rock: Sponges in the Ecosystem

Despite their unassuming appearance, sea sponges are ecological powerhouses, contributing significantly to the health and biodiversity of marine environments.

- Water Filtration and Clarity: As discussed, their filter-feeding activities remove suspended particles, bacteria, and detritus from the water, improving water clarity and quality. This is particularly important in coral reef ecosystems.

- Habitat Provision: The complex structures of many sponges provide shelter, camouflage, and breeding grounds for a myriad of other marine organisms, including small fish, crabs, worms, and brittle stars. Some sponges even host symbiotic algae or bacteria.

- Food Source: While not a primary food source for many animals due to their spicules (skeletal elements) and chemical defenses, certain specialized predators, such as sea turtles (especially hawksbill turtles), nudibranchs, and some fish, do feed on sponges.

- Nutrient Cycling: By consuming organic matter and releasing dissolved nutrients, sponges play a role in nutrient cycling, making nutrients available to other organisms in the ecosystem.

- Bioerosion: Some sponges, known as excavating or boring sponges, can bore into calcium carbonate substrates like coral skeletons and mollusk shells. While this can be destructive, it also contributes to the recycling of calcium carbonate and creates new habitats.

Friends and Foes: Interactions with Other Marine Life

Sponges are not isolated entities; they engage in a complex web of interactions with other marine organisms.

- Commensalism: Many small invertebrates, such as crabs, shrimp, and various types of worms, find refuge and shelter within the intricate canal systems of sponges. These relationships are often commensal, where the guest benefits without significantly harming or benefiting the host.

- Predation: As mentioned, certain specialists have evolved to overcome sponge defenses. Hawksbill sea turtles have narrow, pointed beaks perfectly adapted for prying sponges off reefs. Nudibranchs (sea slugs) are also known sponge predators, often incorporating the sponge’s defensive chemicals into their own bodies for protection.

- Competition: Sponges compete with corals and other sessile organisms for space on the seafloor, particularly in reef environments. Their ability to grow rapidly and produce chemical deterrents can give them an advantage in these competitive interactions.

Sponges and Humanity: A Timeless Connection

The relationship between humans and sea sponges is ancient and multifaceted, extending from practical applications to scientific discovery.

- Historical Use: For millennia, natural sponges, particularly those from the genera Spongia and Hippospongia (bath sponges), have been harvested for their soft, absorbent skeletons. Ancient Greeks and Romans used them for bathing, cleaning, and even as padding for helmets.

- Modern Applications: While synthetic sponges have largely replaced natural ones for many uses, natural sponges are still valued for their superior absorbency and softness in specialized applications, such as fine art, ceramics, and cosmetic industries.

- Medicinal Potential: Sponges are a rich source of novel biochemical compounds. Many species produce potent secondary metabolites as defense mechanisms against predators and competitors. Scientists are actively researching these compounds for their potential as antibiotics, anti-inflammatory agents, and even anti-cancer drugs. This field of marine biodiscovery holds immense promise.

- Environmental Indicators: The presence, health, and diversity of sponge populations can serve as indicators of water quality and ecosystem health, making them valuable subjects for environmental monitoring.

- Bioerosion and Infrastructure: While beneficial in natural ecosystems, boring sponges can sometimes damage human infrastructure, such as oyster farms or submerged historical artifacts.

Ethical Encounters: What to Do if You Find a Sponge

Whether you are a casual beachcomber or an avid diver, encountering a sea sponge in the wild is a special moment. It is crucial to remember that these are living animals, and their well-being depends on our responsible behavior.

- Observe, Do Not Touch: Admire their beauty and unique forms from a distance. Touching a sponge can remove its protective mucus layer, making it vulnerable to disease, or damage its delicate cellular structure.

- Leave in Place: Never attempt to remove a living sponge from its attachment point or take it home. Sponges quickly perish out of water, and removing them disrupts the ecosystem.

- Report Unusual Sightings: If you notice signs of disease, bleaching, or unusual damage to sponges in a particular area, consider reporting it to local marine conservation authorities or research institutions.

Caring for Captive Sponges: A Zookeeper’s Guide

Maintaining sea sponges in captivity, whether in public aquariums or for research, requires a deep understanding of their specific environmental needs. Zookeepers and aquarists play a vital role in ensuring their health and longevity.

- Water Quality is Paramount:

- Salinity: Maintain stable marine salinity levels appropriate for the species.

- Temperature: Keep water temperature within the species’ natural range, avoiding sudden fluctuations.

- pH: A stable pH, typically around 8.1-8.4 for marine species, is essential.

- Filtration: Robust mechanical and biological filtration systems are crucial to remove particulate matter and maintain low nutrient levels, mimicking their natural, clean water environments.

- Water Flow: Provide appropriate water flow to facilitate feeding and waste removal, but avoid direct, strong currents that could damage the sponge.

- Diet and Feeding:

- Microscopic Food: Sponges require a constant supply of microscopic food. This typically involves regular dosing with phytoplankton, zooplankton, and specialized liquid invertebrate foods.

- Frequency: Frequent, small feedings are often better than large, infrequent ones to maintain water quality.

- Substrate and Placement:

- Secure Attachment: Provide a stable, inert substrate (e.g., live rock, ceramic frag plugs) for the sponge to attach to.

- Avoid Air Exposure: Sponges are extremely sensitive to air exposure. Even brief contact with air can cause irreparable damage to their internal structures. Handle them underwater whenever possible, or keep them submerged during transfers.

- Handling and Maintenance:

- Gentle Touch: If handling is absolutely necessary, do so with extreme gentleness, preferably with gloved hands to avoid transferring oils or contaminants.

- Observation: Regularly observe sponges for signs of stress, disease (e.g., tissue necrosis, discoloration), or detachment.

- Quarantine: New sponges should always undergo a strict quarantine period to prevent the introduction of pathogens or pests into established systems.

Fascinating Facts About Sea Sponges

- Incredible Longevity: Some deep-sea sponges are among the longest-living animals on Earth, with certain species estimated to live for thousands of years.

- Regenerative Masters: Sponges possess an extraordinary ability to regenerate. If a sponge is broken into tiny pieces, each piece can potentially reassemble itself into a complete, functional sponge.

- Powerful Pumps: Despite their lack of a heart, sponges are incredibly efficient pumps. A medium-sized sponge can filter hundreds to thousands of liters of water per day.

- Diverse Forms: Sponges come in an astonishing array of shapes, from encrusting mats and delicate fans to massive barrel shapes and intricate branching structures.

- Chemical Defenses: Many sponges produce a wide variety of bioactive compounds that deter predators, prevent overgrowth by competitors, and protect against pathogens. These chemicals are of great interest to pharmaceutical researchers.

- Glass Sponges: Some deep-sea sponges, known as glass sponges, construct elaborate skeletons made of silica (glass) spicules that can be incredibly intricate and beautiful.

From their ancient origins to their vital ecological roles and their potential for future human benefit, sea sponges are truly remarkable creatures. They remind us that complexity and importance in the natural world do not always come in the most obvious packages. The next time you encounter one, take a moment to appreciate these silent, sessile wonders, the unsung heroes of our underwater world.

![Red Angus Closeup of a beautiful Red Angus cowPhoto by: U.S. Department of Agriculture [pubic domain]https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/](https://animals.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Red-Angus-4-100x75.jpg)